What Ridiculous Things We Could Ask of Each Other Over Time

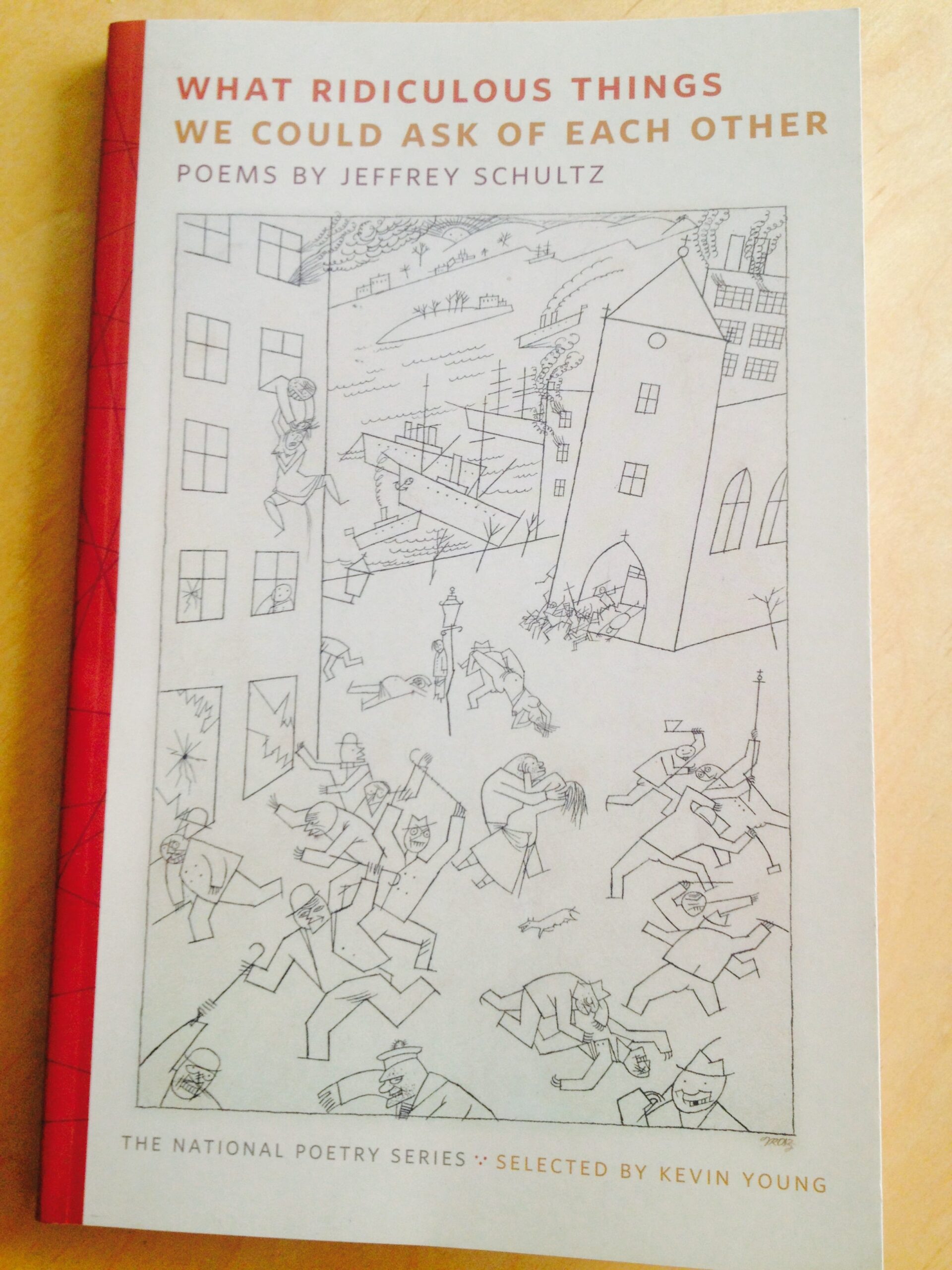

I put off reading Jeffrey Schultz’s What Ridiculous Things We Could Ask of Each Other for a good three months. I propped it up on my desk and looked at it a lot, though. I studied the 1915 line drawing by George Grosz on its cover, titled Riot of the Madmen. It’s unclear whether the madmen have descended upon the town or are its usual inmates: One dangles a terrified woman from a two-dimensional window; others charge through the streets with canes and hatchets. Knowing that Grosz worked in Germany during WWI makes the drawing’s connection to war unavoidable. Only a book that attempts to look at social cruelty square in its maw would have rape, murder, and war pressed flat on its cover. And I am a coward. Reading the news and sorting through an inbox full of social change petitions make me feel ill most days. A book that looks ready to enumerate yet more ways the world sucks right now inspires procrastination.

I put off reading Jeffrey Schultz’s What Ridiculous Things We Could Ask of Each Other for a good three months. I propped it up on my desk and looked at it a lot, though. I studied the 1915 line drawing by George Grosz on its cover, titled Riot of the Madmen. It’s unclear whether the madmen have descended upon the town or are its usual inmates: One dangles a terrified woman from a two-dimensional window; others charge through the streets with canes and hatchets. Knowing that Grosz worked in Germany during WWI makes the drawing’s connection to war unavoidable. Only a book that attempts to look at social cruelty square in its maw would have rape, murder, and war pressed flat on its cover. And I am a coward. Reading the news and sorting through an inbox full of social change petitions make me feel ill most days. A book that looks ready to enumerate yet more ways the world sucks right now inspires procrastination.

And yet, after actually reading Schultz’s poems, that tension between procrastination and facing cruelty head-on seems to be part of the point. What I took at first to be a question in the title: “What things could we ask of each other?” instead reveals itself to be a compendium. These poems contain possibilities and observations, askings and responses. They gesture towards infinite moments of requests and multiplicities of answers. These poems scope out a world through its continuities of radios, kitchen tables, morning coffee with subpar rolls, cars with subwoofers, cancerous off gasses, chemical coatings, and auras of substations. They offer us, refreshingly, images of a world not obsessed with the digital, grounded instead in electrical, sensory perceptions. Life in these poems operates in proximity to air conditioners, laptops, and radios, but not within them.

“Power Outage, Fresno, California, August 10, 1996” in particular gives us people physically slammed by summer heat and then dazed by the slight coolness and unaccustomed quiet of a blackout dusk,

Cooler, finally, outside than in, everyone’s laid out broken

On the stoop with half-warmed beers or sun tea and what’s left

of the ice, or else they wander in dazed pairs on the older,

Tree-lined streets. There isn’t a single siren or gunshot,

not the rattle of a distant argument or an air conditioner’s hum.

These people are damaged, “broken” and “dazed,” by their circumstances, yet they have contact with each other in the unusual malfunction of their routines. Schultz narrates this evening in which he is young, unknowingly walking with his future wife and innocent of the bureaucratic drudgery of his future. The poem ends with a meditation on our intense, human experience of the present moment, its satisfying enormity,

It’s absolutely everything charged into absolutely

nothing more than the dulled, relentless fever

Of now, which presses so hard we can’t help but feel filled.

I read What Ridiculous Things We Could Ask of Each Other the first time lying in bed on a rainy midwinter morning when it seemed likely that it would never again be possible to read by daylight without supplemental lamps. The next time that I read back through the book, pausing and lingering over poems for a second or third time, the students in my morning English 101 class were sleepily, albeit good-naturedly, bent over a peer response activity. As I type this, it’s Saturday afternoon and there’s a bluer sky than anyone has a right to expect during a Pacific Northwest March. Sometimes things progress unexpectedly, and unexpectedly beautifully, for no particular reason. In “The Soul as Episode in the Supermarket,” Schultz writes about his soul ascending irrepressibly upward and outward in the middle of the mundane, ersatz signifiers of a grocery store, in the middle of the “plasticized recreation” of the meat department and “piped-in thunderclaps” of Produce. Schultz reports,

He’s in the esophagus, a talon lodged

in the trachea. I grin like an idiot, ready to buckle at the knees.

Sometimes the unexpectedly beautiful is sudden and unavoidable. But even then we have to acknowledge that beauty and progressions don’t make up for what has gone wrong in the world. “Weekday’s Apocalyptic” posits for us the “undocumented workers,” “terrified mothers,” and a figure of the world as a woman bleeding out in a bathtub, her mind drifting somewhere between resignation and defiance. Even among horrors, Schultz seems to be saying with these poems, a soul’s joys are absurd and implacable.

What Ridiculous Things We Could Ask of Each Other, published in 2014 by the University of Georgia Press, is Jeffrey Schultz’s first collection. His poems have appeared in Boston Review, Missouri Review, Prairie Schooner, Poetry, and other journals including the Bellingham Review. He has received the “Discovery”/Boston Review prize and a Ruth Lilly Fellowship from the Poetry Foundation. Schultz teaches at Pepperdine University in Los Angeles.

KATELYN KENDERISH is a poet and MFA student at Western Washington University. She is a poetry editor for the Bellingham Review.