Pansy That!

A Review of Andrea Gibson’s 2015 Book of Poetry, Pansy

by Jocelyn Marshall

Who buys books of poetry these days—especially performance poetry that’s meant to be watched and heard? Other spoken word poets, right? (And maybe a few other non-poets willing to spare the funds—myself included.) But Andrea Gibson presents a hard sell as they perform their work. After their March 2015 Seattle performance, I waited in the long, snaking line on the ground floor of Neumo’s and handed over the only cash I had on me for a copy of Gibson’s latest collection, Pansy. Although again printed by Write Bloody Publishing, and classic, powerhouse Gibson in nature, this newest collection includes an unexpected dose of heavy race-class social justice commentary—leaving readers floundering amidst layers of inspiring activism, sadness, and hope.

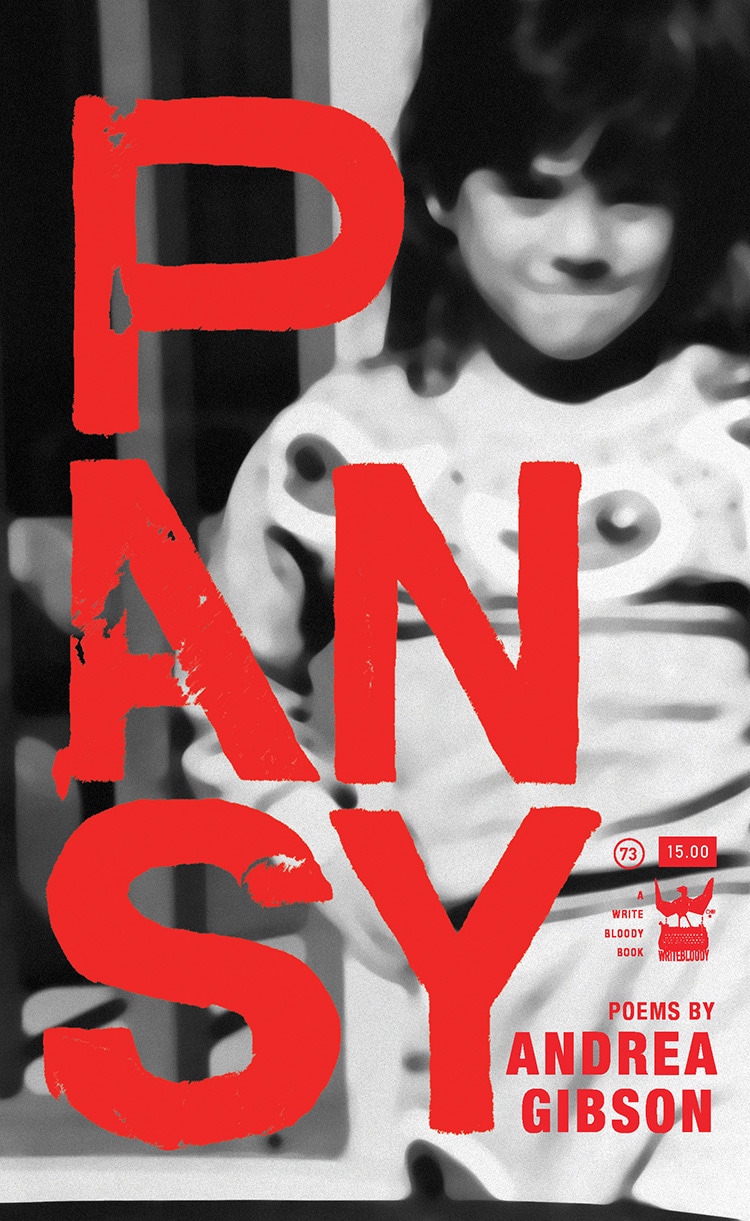

The book’s black-and-white photograph cover and cheeky opening poems are as inviting and entertaining as Gibson’s sweet smile and humble posture were in Seattle, where they captured the audience with the abrupt line: “Tonight, I want to talk about love.” One could feel the bristling hairs and nervous sweat beads gather from the just-friends couples. However, the whole audience soon learned that being surprised by unexpected, poignant statements was a consistent theme of the night. The set mirrored the organization of Pansy, opening with a poem entitled “Elbows,” which encourages readers to embrace the discomfort of increased human connection. This is then followed by the silly “A Letter to My Dog Exploring the Human Condition,” where all are invited to laugh at human oddities and pine over Gibson’s well-articulated love for their pet.

Yet, after a few introductory pieces, the collection’s sweet feel-goods are sharply interrupted by “A Letter to White Queers, A Letter to Myself.” Following the pattern and rhythm of Pansy, Gibson broke their “talk about love” in Seattle with this piece, and the room immediately became quiet—converting the audience into attentive, motionless drones. The predominantly white, queer audience paused in unison to reflect on the bold and matter-of-fact phrases deftly embedded into each line, and the just-friends couples broke down to reach out for a hand to hold. Gibson’s heart-wrenching pain and shame in the failure of their community and themself landed on equally heavy hearts.

Later, when reading the collection at home, the same poem similarly broke my happy, love-filled Pansy experience, caused my pen to sit still—for once—and I became clueless about what to think and annotate. I was taken aback by the eerie descriptions, like “I could feel the last bit of unburied faith swallowing the gravel in the dug-out grave of my chest,” while being simultaneously slapped by stark statements of “White is having all of Eric Garner’s air in your lungs” and “Our silence is not a plastic gun. It is fully loaded.” From that prose piece, Gibson then guides speechless, wordless readers like myself to a heartfelt upper, “Angels of the Get-Through.” Readers then pause contentedly at sincerely loving lines like “I am already building a museum / for every treasure you unearth in the rock / bottom” and “Best friend, this is what we do. / We gather each other up.” This volley between provoking reflection, calling for action, and providing hope keeps readers’ brains and hearts tightly on a swivel, often turning sharply. Right when readers think it’s okay to breathe, Gibson subtly deflates their lungs, and then blows air back into them with the poet’s sincere vision of a better world.

With this collection’s form and content, in particular, Gibson’s book mockingly embraces the term “pansy” with its bold, powerful sociocultural commentary. As the LGBTQ community is as much of a stranger to the word “pansy” as it is to “queer,” Gibson re-presents this word, this concept, with a showcase of power behind the poet’s striking vulnerability and reflection. Their previous collections The Madness Vase and Pole Dancing to Gospel Hymns are similarly introspective and primarily grapple with aspects of queer identity and trauma. However, despite these new pieces rooted plainly in Gibson’s characteristic self-analysis, Pansy reaches outward further than other collections have before—acknowledging the shortfalls of being concerned about only one kind of community. Instead, Gibson, clearly impacted by the increased visibility of police brutality and flawed justice systems, widens their platform to include issues of race and class.

Using a somewhat shock-value technique, Gibson presents social justice content in several forms: “A Letter to White Queers, A Letter to Myself” and “Privilege Is Never Having To Think About It” are prose poems prefaced by brief blurbs; “Ferguson” and “Riot” are short, two-lined pieces; and “Lens” and “07/13/2013, Journal Entry: George Zimmerman Found Not Guilty” are shame-filled, debatably apologetic poems in verse. Weaving in-between pieces about trauma and love, fear and hope, these abrupt poems are consistently unexpected. The variety in form and content perpetuate a never-fading surprise element with each heavy-hitting section overflowing with critical commentary. For readers, this structure acts as a spotlight for the take-away message(s) in these race-class concerned pieces—a seemingly new direction for Gibson in response to recent social and political events.

However, to reduce Pansy to a one-dimensional social justice focus would leave the other layers at work unacknowledged. Gibson, as they suggested in the opening of their Seattle performance, does “talk about love,” as well as trauma, feminism, and silliness. Pieces like “Exploring My Relationship History” and “On Being the Blow Job Queen of My High School” will make one giggle like a small child, while “Emergency Contact” and “Royal Heart” will prompt readers to pull significant others close. For riling up feminist fans, Gibson presents “To The Men Catcalling My Girlfriend While I’m Walking Beside Her” (which, when performing in Seattle, they had to re-start the poem three times, explaining “I’m not mad enough” out of frustration before a successful final attempt). And for convoluted anthems of self-reflection and self-acceptance, “Prism” and “Pansies” offer readers relatable spaces of vulnerability.

This unique tapestry of Pansy, with its poems varying in form and content, collectively voices a call for direct action and presents a vision of a more peaceful world. Arming readers with love and support, Gibson’s poems do more than present the perspective of a “white queer”; instead, they simultaneously scream about injustice, discuss abuse, and promote the simple pleasure of being called “Honey.”

JOCELYN MARSHALL is an animal-loving, creative nerd. Sometimes, she reads, teaches, and writes for social justice, with a particular interest in the fields of gender, sexuality, and transnational feminism.