The False Comfort We Spun

So many things about you I didn’t know. I suppose that is what happens when a grandmother dies. After all, I was only 18 when you left that day in May. All my teenage years you asked me if I had a boyfriend––no, sort of, not yet––now I understand perhaps behind the question was the yearning to fulfill the romance you never could.

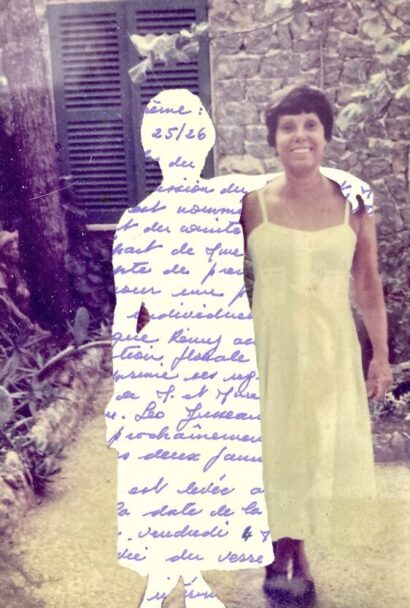

Jorge, I found out, was his name. I know almost nothing about him except that there was an ease of your smile and posture in the photos where you’re near him. And that his Catalan mother Joaquina was your mother’s friend. When I ask about him, your twin sister, my Tatate, says “No lo se.” Though he was your boyfriend once, this she knows. She is 93 now and her memories are few and fading. I look into her beautifully wrinkled face and see what yours would have looked like. She is still as elegant as I’d always remembered you––white hair perfectly styled, decorated cashmere scarf, gold earrings, leather loafers. And like you, her Spanish is accented French, from your French mother. I ask her if she thinks primarily in Castellano or French. Castellano, she says, without hesitation. I ask her all the questions I can no longer ask you.

I ask what you liked to cook. Did you make sopas mallorquinas, paellas, cocas, tortilla de patatas and smear tomatoes over sourdough bread like my mother, your daughter did? I find out that growing up poor during the war you learned to make the simple things. Bechamel sauce, croquetas (though croquetas are not so simple to make, you know). You were nervous to make tortilla española because you were afraid of turning it over. Other things you were afraid of included: flying, Papi Leo’s anger filling the room, how his temper made you tamper your own being, and death. That I remember. You didn’t want to believe it when it was happening to you.

Fears I inherited from you: take offs and landings, the flip of the tortilla, anyone’s temper. I never miss an annual checkup, urge those I love to do the same. I, too, fear they will find a lump. That it will be too late.

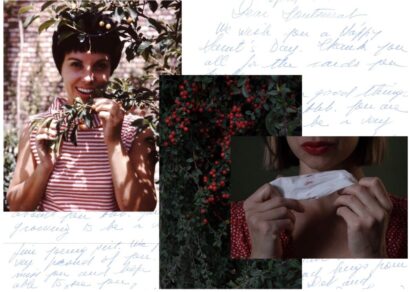

Would you remember today that when I was just a little girl, you’d sing: Que Sera Sera, in your native Spanish? What I remember most was the way you’d paint your pale lips the color of your country’s flag, over and over again before and after you sang. The moment before red, there was no color at all.

I took note. I rarely wore lipstick as a girl, teenager, not even as a woman. I wanted to cling to the natural blush of my lips as long as I could. A facade of control, another thing we shared, this false comfort we spun. What was it in you, that is also in me, that believed if we only told ourselves things were fine, they would be? That if we went to the doctor, said the right thing, in the right tone, wore lipstick, or avoided it altogether, everything might turn out alright. I wish I could tell you that today, I paint my lips red with abandon. Letting go, I think of you. Whatever will be will be, you sang. Que sera sera.

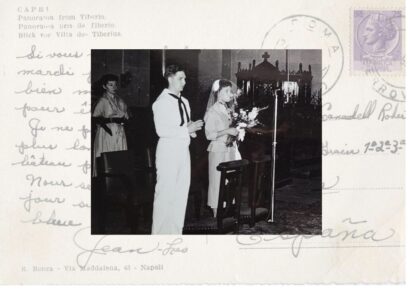

The last time I saw Papi Leo, months before he died at his nursing home, he had a photo of you two–him in his navy suit and you not a button missing or a curl out of place. “How did you meet?” I had never thought to ask anyone. He couldn’t remember what he’d had for lunch that day, but the story of how he met you, this he had clear. He began to tell me: he worked as an interpreter in the Navy and knew all the love affairs going on, as he would translate letters from French into English for everyone. As he was reading the letters written in French from you, to his friend, he started to develop interest in you himself, finally asking the friend if he could write to you. After two years of writing to each other, you finally were able to meet in person when his ship posted in Spain. After more courtship, you married in Algiers, he told me. Que romantico, I thought. If only the marriage had been romantic, too.

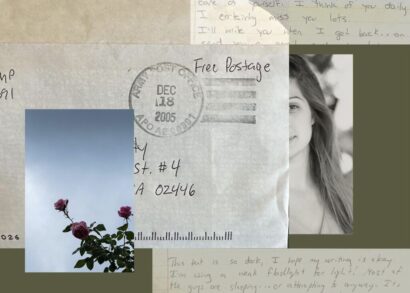

When I was 22, a few years after you died, I began an epistolary romance of my own. This boy showed me an uncomplicated love I hadn’t known before. I had met him in person only once, briefly, when a mutual attraction couldn’t be realized as he had a girlfriend, a Miss America type as I remember. We mostly lost touch, but as fate would have it, we connected again by email in the fall after I graduated college. “You won’t believe this, but I just arrived in Iraq,” he wrote in that first note. If I could send him a letter, a photo, it would make him so happy, he said. That same day I put pen to paper and searched for recent photographs.

And so it began. He was in the military police reserves and had been called to serve in the army during the invasion of Iraq by the United States. We wrote letters to each other almost every day for a year––him under “weak flashlight,” he’d sometimes tell me, and me under the fluorescent lights of an office–– and in these letters our romance began to bloom.

Later, when he’d returned and we reunited in the flesh, his mother told me he’d swiftly declared “she’s the one.” The one. Those two words made me nervous, but I pushed aside my doubts in order to fit the narrative of a perfect romance. I wonder if you, too, had those doubts early on. And whether, like me, you ignored them. The seeds of our mismatch began to sprout in the early days of our courtship. How could we be together, I once joked, when I loved pasta so much, and he hated it? “I’ll learn to like it,” he’d said, with seriousness. His mother told me of the books he’d collected on his nightstand. “Those are for you, you know. Before he met you, he rarely read.” I was both touched that he’d made an effort to take on my interests, and sad thinking I was pushing someone to manufacture them. But he was gentle, and kind. He brought me flowers, soothed my anxieties, and one day put a white gold necklace around my neck as he told me: “You kept me alive while I was out there, you know. The thought of coming home to you was what kept me going.” It pleased me to know I brought him some light in that darkness, but I couldn’t explain why I sometimes flinched from his touch. He felt this resistance too, and I knew it hurt him. “But I don’t want to go to Spain” he’d meekly said, once we were together close to a year. Spain was half of me, and he had no interest in knowing that part. He couldn’t force it, like he’d tried the books and pasta. He’d saved up money for a ring he never gave me. Sometimes, I wonder what might have happened if I had swept my doubts aside and married him. What would have happened if you hadn’t married Leo, had listened to yours.

Every summer, you’d take me shopping for a new outfit. As I wore almost exclusively thrift store clothes and hand-me-downs, this annual trip thrilled me. One late August at Limited Too, you told me to never rely on a man for money. You told me this, as you were counting the dollar bills in your wallet, as you had to account for every one of them you handed over. They were not yours to spend freely. I felt this gravity when I wore my new shirt to school that fall. I also remember how you protected me when Papi Leo’s temper would inevitably begin to flare. To escape, you’d take me to the movies, always romances which we’d both enjoyed because, perhaps, they allowed us a few hours suspended in a fantasy of a life we’d both wished for.

I went to visit you today at the cemetery in Deià. There is a new cat in the village–speckled black and white and he follows me to you, circles my calves. He charms everyone, you would have loved him of course. I imagine you walking the pebbled pedra en sec with Jorge, hand in hand, your red lips blooming towards that smile. A smile that might not have faded. What if you had stayed with him here, after all?

All those letters you wrote to Papi Leo, those I wrote to my own love, and here I am writing another, this time to you. Like the others, this one will also ultimately disappoint, because you will never read these words. What I didn’t yet know as a young girl––that there was more to love than what we saw on the screen. What I mean to say is that what we had been reaching for we might have already had. That a great love, too, could be between a grandmother and her granddaughter. What I didn’t know until now––the way your story would echo through my own; the way I would keep finding reasons to love you, decades after you’ve gone.

I imagine you asking me today, “Do you have a boyfriend?” No, but when I do, he will be, I hope, my own Jorge. And I’ll always make sure when I count my dollars, they are my own.

Montserrat Andrée Carty is a Spanish-American writer and visual artist. In addition to writing and making photos, she hosts the podcast Musings of the Artist and is the Interviews Editor for Hunger Mountain. She has a MFA in Writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts and is currently working on a hybrid essay collection on home and belonging.