Gore, Grit, Gristle, Bone

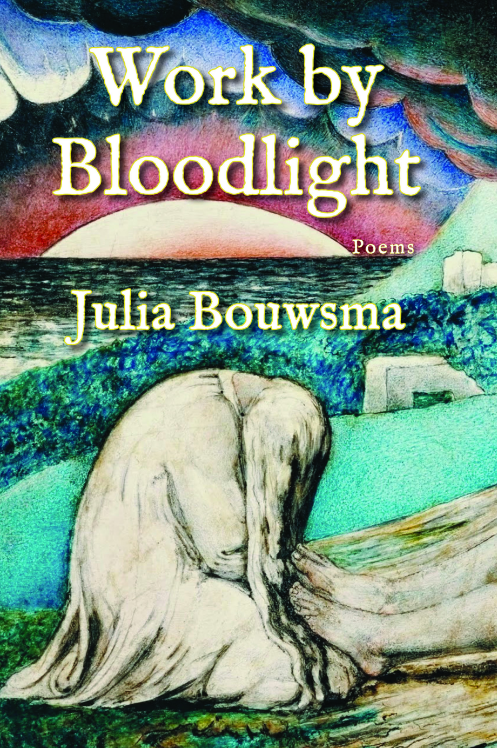

Work by Bloodlight, by Julia Bouwsma

Winner of the 2015 Cider Press Review Book Award, Linda Pastan (Judge)

Cider Press Review, 2017

Reviewed by Dayna Patterson

Bouwsma’s poem “We Are Just Three Mouths” appears in Issue 73 of Bellingham Review, which you can read here.

Bouwsma’s poem “We Are Just Three Mouths” appears in Issue 73 of Bellingham Review, which you can read here.

In the darkest fairy and folk tales, there is the hollow sound of wood chopping to comfort abandoned children. There’s a wolf waiting in forest shadows for a red hood. There’s an intricately carved box meant to hold a girl’s insides, but a pig heart glistens in its stead, warm and leaking. In Julia Bouwsma’s debut poetry collection, Work by Bloodlight, readers will find the hungry children, the predators, the pig heart steaming in its own reek, and precious little comfort. This is a book of gore, grit, gristle, bone. A brew of blood, shit, piss. Blending grimoire and Grimm, myth and memory, these poems invite readers in with a mesmerizing and menacing “Spell for Spring” with its witch-like beckoning to

. . . Come closer.

A cluster fly drowns in the sap pail. Now you will crave

the taste of dirt under your fingernails. In your teeth. Throat.

You will learn to swallow your hands. (3)

Like Bouwsma’s poems themselves, the spring season both “burbles song over your boots” and brings the cat to the doorstep with “a flying squirrel, half carcass on the front porch seeping rain” (3). There is both a beauty and rawness to Bouwsma’s lines that echo the epigraph to the book:

Not a cruel song, no, no, not cruel at all. This song

Is sweet. It is sweet. The heart dies of this sweetness. –Brigit Pegeen Kelly

The heart dies of sweetness the way the fly drowns in sap, the way mud burbles and the carcass seeps rain. Subsequent poems force a reckoning, a brute honesty between past and present; between the act of slaughtering and what we see prettied up at table; between reckless fathering and the thorny wilds of childhood.

Two major threads in this collection are a series of elegies, with haunting titles such as “Elegy as Invocation for Ghosts,” “Elegy as Bonfire,” and “Elegy as Long Skin,” and a series of poems about the speaker’s father, referred to as “The Calligrapher.” The elegy poems are rich and strange and dark, a damask of nightmare and conte de fées:

Hollow, I take to the woods road after dark, squat and piss

in the clearing under the open-mouthed moon, down

a bottle of stout while my little black shepherd forages—frozen apples

in the slash-field. Every shadow is a pile of rocks. Every rock

is an invitation for your hands to reach out and grab me

for lingering here—in this frozen wreckage, land hewn

of our spalting memory—(31)

In the second thread, the father called “the Calligrapher” garners his peculiar metonym in the first of this series, entitled “We Go on Vacation; the Calligrapher Stays Home.” Calligraphers draw beautiful lines, but in this case the father makes lines of coke, which he “snorts through a half-formed calligraphy pen” (17). If the family unit in Bouwsma’s collection is a stump in the woods with a rot-softened core, that central decay would be the father, and the speaker-daughter is a sapling that, side by side with her sister, manages to grow out of and despite a parent’s slow moldering.

Bouwsma lives and works on an off-the-grid farm in Maine, and these poems incandesce with her experience working by bloodlight in “the bullet dawn“ (50). If there is redemption to be found in this collection, it is hard earned and leaves bone bruised. It eschews pity (“Pity is a child’s outstretched hand, the cicada shell still clinging”) and dons thick muck boots to declare “What strange and wonderful beasts we are” (45).

DAYNA PATTERSON is the Managing Editor of Bellingham Review, Poetry Editor for Exponent II Magazine, and Editor-in-Chief of Psaltery & Lyre. Her poetry has appeared in North American Review, The Fourth River, Literary Mama, Weave, Clover, and others.