Contributor Spotlight: Jenna Butler

Jenna Butler’s essay “Translating the Woods: Life in the Northern Canadian Boreal” is part of the special international section “Place & Space in Canada” in Issue 74 of the Bellingham Review, which will be available mid-April 2017. Subscribe or purchase a single issue through our Submittable page here.

Jenna Butler’s essay “Translating the Woods: Life in the Northern Canadian Boreal” is part of the special international section “Place & Space in Canada” in Issue 74 of the Bellingham Review, which will be available mid-April 2017. Subscribe or purchase a single issue through our Submittable page here.

What would you like to share with our readers about the work you contributed to the Bellingham Review?

My personal essay for the Bellingham Review delves deeper into an issue I’ve been thinking and writing about for some time: the changing face of the boreal forest in northern Alberta. With the impacts of climate change becoming more and more noticeable in the earlier and longer fire seasons each year, and with the 1,500,000-acre Fort McMurray fire in May of 2016 driving home just how vulnerable this changing ecosystem is becoming, my essay focuses on lessons learned from the boreal landscape during the creation of the off-grid organic farm in northern Alberta that I call home. Working with this rapidly changing, and soon to be threatened, boreal locale, my husband and I have striven to create a diversified human-powered farm that looks to the untouched land outside the fence of our market garden to inform our growing and planting practices.

Is there a Canadian aesthetic to writing about place and space? What impact does that have on your writing?

I think we absolutely consider place and space in much of our writing (though this preoccupation has also been used to sideline Canadian writing as always about “the weather” or “the land”). In Alberta, the place I call home, the deep cold of our winters often turns us to consider the landscape because the land informs our day-to-day survival, especially if you live life off the power grid, as I do for much of the year. In this case, considering place and space is as much about function as it is aesthetic.

I also wonder if the Canadian aesthetic consideration of place and space is the result of being a blended country with a number of influences at work: Aboriginal narratives of land, culture, and belonging; settler narratives of displacement, change, and rooting; and recent influxes of immigrants and refugees, whose narratives often take the form of stories about lands and homes lost, left behind, and the necessity of new groundings.

Tell us about your writing life.

I have been writing professionally for over two decades, and the land is a major part of the reason I’ve kept writing. Working with and living on the land proves endlessly engrossing, especially in light of climate change narratives I experience daily as a small-scale farmer. While I work on the land, I also teach about environmental literature, and I research and write within the field of ecocriticism. The land draws these three threads of my life into alignment.

At its essence, all of my work comes back to considering landscape and home, but the genre I employ is in constant flux, from poetry to fiction, memoir to academic essays. This, too, helps to keep me engaged.

Which non-writing aspect(s) of your life most influences your writing?

The land in northern Alberta that I am grateful to call home, and all the layers of story that it holds.

What writing advice has stayed with you?

Denise Riley: “Who I am is nothing to the work.” When we talk about land, we need to stay open, to realize that there are many stories of belonging on a plot of ground. We tend to want to talk about our own experience, but our tale of belonging is often just one of many; the concept of home is layered, complex. Although I often write personal essays rooted in the land my husband and I call home, I’m also very aware of the strata underwriting our narrative there. I’m learning to be open to story, to listen to those various histories from willing tellers.

What is your favorite book(s)?

Favorite writer(s)?

Today, right now? Joy Harjo’s brilliant poetry collection She Had Some Horses.

What are you reading right now?

It’s nearly spring, so I’m reading according to my yearly cycle of texts that shift the season for me. Lorine Niedecker. Wendell Berry. Di Brandt. Louise Bernice Halfe (Sky Dancer).

What project are you working on now?

I’m currently finishing a travelogue connecting the Norwegian Arctic, where I lived over the summer solstice a few years ago, with the northern Canadian boreal in terms of environmental damage. And I’m partway into a book of essays about women, beekeeping, and international community-building.

Anything else our readers might want to know about you?

When I’m not teaching, you can find me out at our off-grid farm in the woods, where I grow and preserve most of our food for the year and practice martial arts. As my students like to tell me, I’m ready for the zombie apocalypse…

Where can our readers connect with you online?

www.jennabutler.com is my personal site. www.larchgrovefarm.com is our farm site. I’m on Facebook as Jenna Butler.

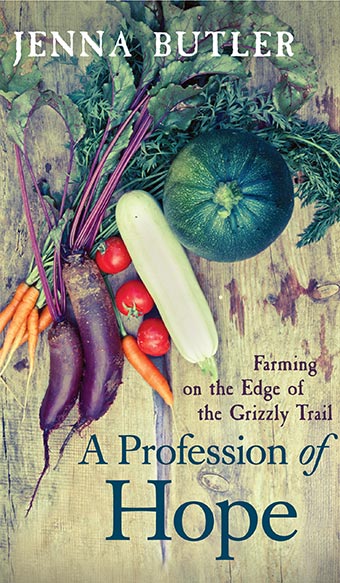

JENNA BUTLER is the author of three award-winning books of poetry, Seldom Seen Road, Wells, and Aphelion, and a recent collection of ecological essays, A Profession of Hope: Farming on the Edge the of Grizzly Trail. Her upcoming books include Magnetic North, a travelogue linking the Norwegian Arctic and the northern Canadian boreal, and Revery: A Year of Bees, essays about women, beekeeping, and international community-building.

Butler’s research into endangered environments has taken her from America’s Deep South to Ireland’s Ring of Kerry, and from volcanic Tenerife to the Arctic Circle onboard an ice-class masted sailing vessel, exploring the ways in which we impact the landscapes we call home. A professor of creative writing and ecocriticism at Red Deer College in Canada, Butler lives with three resident moose and a den of coyotes on an off-grid organic farm in Alberta’s North Country.