Abra: The Kinetic Page

by Amaranth Borsuk

Video Transcript:

When she visited Seattle in the fall of 2014 to install The Common S E N S E, a large exhibition at the Henry Art Gallery, Ann Hamilton spoke at my campus’s annual Convergence on Poetics, a rare and resonant gift that continued after she left through the exhibition itself, which fused the university’s many archives in a single space: bringing together the Burke museum’s taxidermies, the Henry’s historic textiles, and Special Collections’ children’s books under a single roof.

○

The Common S E N S E explored “touch” as a means of bridging the boundary we set up between ourselves and the world. It was intimate and expansive at once. As I walked through the upper galleries, where newsprint images of the undersides of birds and small animals fluttered in the HVAC breeze, I thought about the way the exhibit invited us to read space. Hamilton’s juxtapositions, like the lines of a poem, rely on the visitor to bridge the between with their body. We provide the spark that leaps across the enjambed line where the tale of Cock Robin meets a downy hide.

○

I’ve strayed from what I wanted to tell you because Hamilton’s work requires it. It is, as she says, a form of attention she seeks to share with her audience—she creates installations as spaces animated by the viewer. She sets up the conditions for an experience or interaction, and then withdraws, trusting the reader / viewer / visitor to make meaning. To limn the contours of the work with their own gentle touch.

○

As I trace my finger along Abra’s cover, whose title is also the incipit, silently voiced by the reader, which activates the text, I’m invoking not only the magic word that brings things to pass as they are spoken, I’m invoking Hamilton, whose “handseeing” videos of the late 90s and early 2000s turn the fingertip into an eye, uniting reading and writing in a gesture that links dactyl and stylus, through the digital that fits like pen in glove.

○

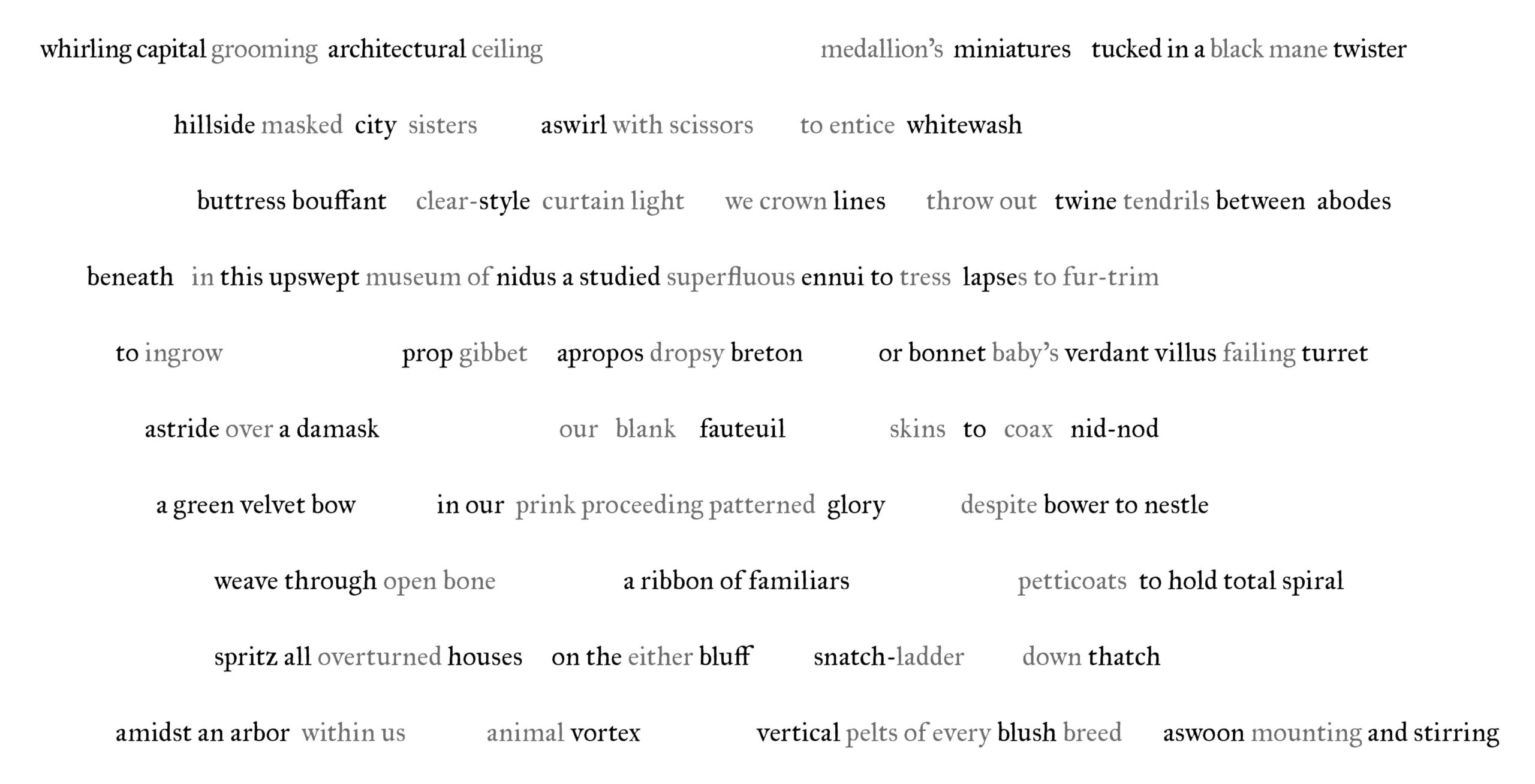

Abra is an unstable, excessive text, one that mutates on the page, blurring the boundary between word and image as poems morph one into the next.

○

When we began this long meditation on collaboration and digital subjectivity, we didn’t know how the book would move, just that we wanted it to exceed us, to press outward and away, a text always in the process of becoming something else. A verso sketch extends toward the recto text, which reaches ever leftward until they interpenetrate: “heaving, tumor trellis up the fleshwall” of this imitation vellum, this machined surface designed to take ink.

○

Flush with gerunds and infinitives, the poem feels its way across the book, a living tapestry woven of words spliced together so that, from one page to the next, the text opens apertures within itself, allowing the words of the next page to appear in its holes: a shifting and shimmering helix of language.

○

Abra refuses to stay fixed. A differential text of which no single form provides an authoritative reading, Abra’s meaning changes with the materials through which we encounter the book. This is not a liquid text that remains the same regardless of its vessel. In every form it changes—a book that overflows.

○

Sometimes a book is a sequence and sometimes it is a substance, and sometimes it is a surface, and sometimes it is a surplus. Its meaning arises through exchange, where the reader’s own finger meets the page, uncovering blind impressions where type has left its mark. This inkless cuneiform registers the kiss of a polymer plate on paper’s surface as fragments coalesce to heave the book into being.

○

In his manifesto for New Lights Press, which makes chapbooks as artists’ books in a lovely studio in Colorado, Aaron Cohick reminds us that such books can only be animated by a reader who “receives the text-book-art-object, and her reading takes it in, uses it up. At the same time she produces the text-book-art-object, putting its paths of meaning into play and driving them outward.”

○

Abracadabra, the page has always been an interface inviting interaction, a manuscript illuminated by the yad of the hot hand of the reader.

○

In Abra, we invite the reader to heat the page and make our words disappear, creating space for their own paths of meaning, providing the mute frame Ulisses Carrion suggested all books aspire to—a white page for the reader’s imagination to populate, much as a scribe revised the borders of medieval manuscripts.

○

We make the book, and it returns the favor, as Carrion observes, its space-time sequence marking our passage from one end to the other as pages deplete. We trace time spatially across the book’s surfaces.

○

The book, after all, is a volume and has volume we seldom notice, save when shot through with luminous apertures, singed along the edge, that let in singing from the floor below.

○

From clay to scroll to codex to tablet, the book’s continuous touchscreen interface beckons us to it. As Lori Emerson points out, an interface is like a “magician’s cape, continually revealing […] through concealing, and concealing as it reveals.” The book captivates us with the infrathin connection it provides between us and language, us and other readers, us and ourselves yesterday, last week, or whenever it was we first encountered it.

○

○

A text animates and mutates under the reader’s fingers, whether digital or print, because each encounter is colored by the reader’s perspective, just as each page is beautifully soiled by contact with the reader’s hand, or face, or sweater, or lunch. The book is an archive of our engagement, and it registers each contact in ways invisible to us. No ornament is truly ornamental—each serves a function, for space or time or aesthetic ends, we orient ourselves to the text with familiar icons. Each fleuron shines, a flash of blush aflame, like phlox or foxglove, beckoning the finger to make it our own, to annotate and customize and take part in the text’s mutation. Abracadabra, the author erects a system and leaves it to the reader to provide the spark that makes meaning, a juxtaposition into which the reader enters, ready to shape this “relentlessly expanding” garden to a trellis of her own design.

○

A book reaches out to the reader who has always been its author.

Dedicated to the students in my Spring 2016 Advanced Interdisciplinary Arts Workshop, Chapbooks and Artists’ Books, with whom I explored the book’s porous boundaries. With gratitude, as well, to Sarah Dowling and the 2016 graduates of the UWB MFA in Creative Writing and Poetics, with whom we took part in Ann Hamilton’s brilliant exhibition The Common S E N S E at the Henry Art Gallery back in 2015.

AMARANTH BORSUK is a poet, scholar, and book artist whose work encompasses print and digital media, performance and installation. Her books of poetry include Pomegranate Eater (Kore Press, 2016); As We Know (Subito, 2014), an erasure collaboration with Andy Fitch; Handiwork (Slope Editions, 2012); and, with Brad Bouse, Between Page and Screen (Siglio Press, 2012), a book of augmented-reality poems. Her intermedia project Abra (trade edition 1913 Press, 2016), created with Kate Durbin and Ian Hatcher, received an NEA-sponsored Expanded Artists’ Books grant from the Center for Book and Paper Arts and was issued in 2015 as a limited edition hand-made book and free iPad / iPhone app. Her other digital collaborations include The Deletionist, an erasure bookmarklet created with Nick Montfort and Jesper Juul; and Whispering Galleries, a site-specific LeapMotion interactive textwork for the New Haven Free Public Library. Amaranth is currently an Assistant Professor of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences at the University of Washington, Bothell, where she also teaches in the MFA in Creative Writing and Poetics.