A Harrowing Collection

Blood Memory by Gail Newman

Marsh Hawk Press (1 May 2020)

Reviewed by Amrit Abbasi

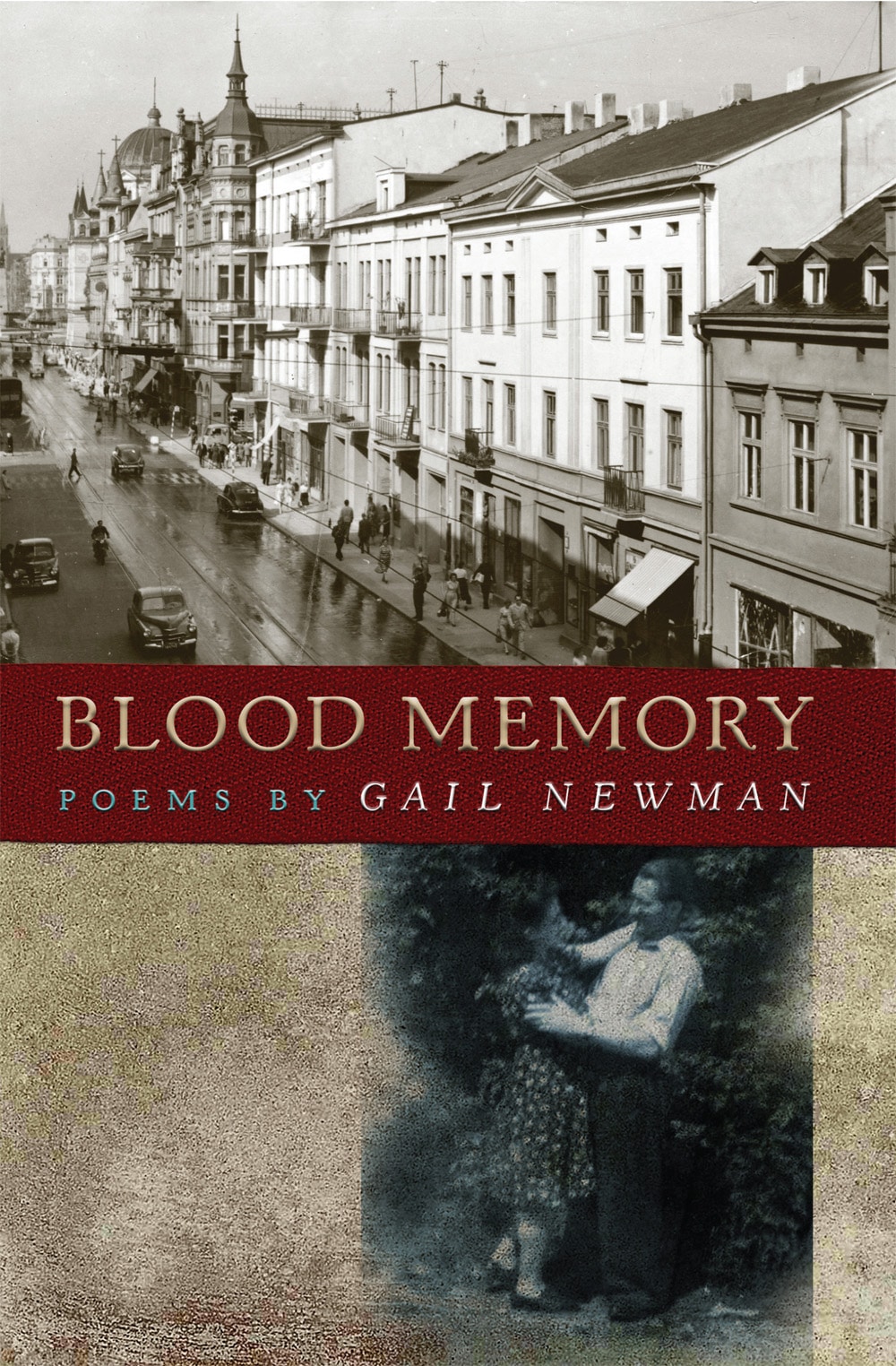

The top half of a nostalgic, beige-y cover displays the streets of Łódź, Poland. The bottom half shows the parents of the author holding each other tenderly. Stretched between is a striking, textured strip of deep red. Burrowed underneath this cover is Blood Memory, poems by Gail Newman, a painful, bleeding history of the author’s family and their lives as Polish Holocaust survivors, intertwined with the insurmountable pressure to normalize after this trauma. Newman brings to life the visceral stories of her family’s journey from Poland to America while her poems leave you breathless and craving more. As her hurt mingles with the torment of her family, she reminds the reader that history is bound to the present just as the present is bound to the future.

Blood Memory is split into three captivating sections: “Blood Memory,” “Lost Language,” and “Living With The Dead.” Newman starts each section with a short poem—an introductory poem if you will—that introduces the reader to the theme at hand. She starts with “Prayer to Remember,” reflecting on how the experiences of those in the Holocaust are being forgotten, writing, “I lay down in deep grass to find solace / beside gravesites sheltered in shadow.” This section shows her readers these forgotten experiences, the shadows slowly giving way to light. She then moves into “I Came into the World” showcasing the life she was born into: “People were singing. The floor shook with dance. / I came into a house where I was a stranger / and was made welcome.” She concludes this poem with “This is mine; this is real,” a concept that struggles to be grasped after trauma. This section, then, reflects on passing on tradition all while trying to survive life after immense trauma, searching for a way to cope. Newman then finishes with “Abandoned Cemeteries,” leading us to a world of death, noting, “No stones or bouquets left in remembrance. / No mourners or words of comfort. / Only the shipwrecked listen, / only the forgotten remember.” She uses this section to write about a shared trauma that’s been dismissed through time, the dead becoming erased. She moves seamlessly through her poems to unravel them, displaying the reality and significance of each Holocaust experience, yet concurrently fuses them together to imagine a trauma that only few can understand. She brings a tremendous question to my mind as her words mingle beneath my skin: What is trauma’s place within time?

Perhaps one of the most resounding themes in Newman’s collection of poems is the idea of home. Utilizing a mixture of Yiddish and English, Newman pinpoints that she herself struggles with the meaning of home. In “Tsebrokhn English,” she writes, “And the English would fade away like smoke / until only the Yiddish remained, and we were foreigners / in our own houses, with strangers for parents.” Resonating with my own life, I think of my parents speaking words of Urdu, my tongue weighed down as I aimlessly try to mimic the shape of their mouths. What is home: my tongue or my heart? Displaced through the Holocaust, her elders also struggle with the meaning of home. In “Two Tales,” a poem dedicated to Newman’s father, his life in the Holocaust stands in juxtaposition with his death. In part one, Newman writes “They took your clothes. / They gave you striped pajamas / in which your body swam / like someone far from shore.” In part two, she writes “They took your clothes. / They put you in a blue gown / tied at the neck like a child’s bib.” At the end of part 1, Newman’s father does the work he is forced to do in an internment camp, while in part 2, the poem ends with him in his mother’s arms, as a child, giggling happily with cherries staining his mouth, his death marking the end of his trauma. Bounced from his childhood, to internment camps, to America, and to his death, Newman conveys that home is as foreign to him as Yiddish is to her.

One of the most striking poems, “Homecoming,” further illustrates the Holocaust’s chilling displacement of home:

My mother came to a dead end called Poland.

The shops gone, the house no longer home.

She knocked at the door. A man answered.

She could see over his shoulder into the living room,

her mother’s lamp, her father’s chair….She asked to come in,

just for a minute to take a breath of the air

that might still carry her

father’s cigarette smoke,the scent of her mother’s soup,

the pencils she sharpened at the desk.

No. No, and again, No.

Words she would carry with her

wherever she went……away

from the street that was not her street,

the city that was not her city[.]

Here, Newman reflects on her mother returning to Poland, her home, only to find that it is no longer her home. Everything she knows, even the home that she has grown up in, has disappeared. The remembrance of the smell of her mother and father drops chills down my spine as the scents swirl around me; they are there, but they are gone, their placement conflated. Newman then smoothly shifts into the next poem, “The Dispossessed,” showing the home, the comfort, and the life both her mother and her father were forced to leave behind. Yanked, removed, plucked forcefully from their homes, Newman unveils the jarring aftermath of the Holocaust.

Newman’s poems force us to confront this pain, anguish, and mourning. She speaks with clarity to unveil a past that we must never allow to seep into the world again. Further, she uses this calculated detail to remind us that we must know and remember the ceaseless torture that others were subjected to; if we forget these victims and their abuse, we erase their experiences and become complacent in their dehumanization. For Newman however, the daughter of pain and trauma, these experiences will never disappear. She writes these poems with an eloquence that demonstrates they never should disappear. She finishes up her last poem, “Blood Memory,” writing, “I stood at the gravesites, feet soaked in mugged earth. / I lay down my body in wet leaves. / I remembered them.” We have a responsibility to remember them, too.

Gail Newman’s Blood Memory is a hard-to-swallow, yet powerful collection that looks across time to bring forth the realities of refugees of the Holocaust, remembering their suffering by entwining it into the present. Though hard to swallow, Newman phenomenally grounds her emotions in a way that connects both to those she’s writing for, and those who she isn’t. We all know pain and trauma, but she forces us to think of it in a way that is outside of ourselves. It’s uncomfortable yet familiar, and both of these emotions pulled me through. A mesmerizing read, you won’t want to put this book of poetry down, finding yourself immersed in it and finishing it as quickly as you picked it up. Then again, not even days later, you’ll find yourself searching for its familiar, haunting cover, ready to sit down and be propelled into it again.

AMRIT ABBASI is an MA candidate at Western Washington University. Some of her interests include ethnic studies, cultural studies, and transnationalism. She’s particularly interested in the roles of women and the LGBTQIA+ community within South Asian literature. Outside of academia, catch Amrit reading novels about race, watching documentaries, or searching the web for stories that give her the heebie-jeebies.

Featured image “Microgravity” by NASA