A Happy Journey

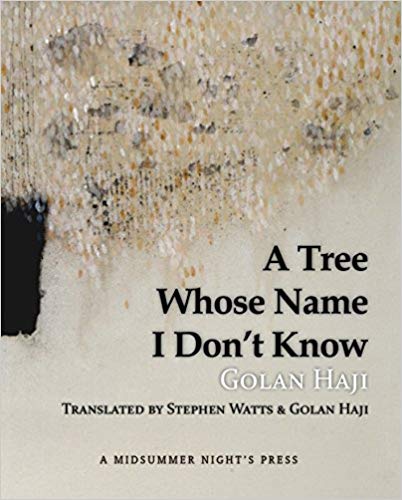

A Tree Whose Name I Don’t Know by Golan Haji, translated by Stephen Watts and Golan Haji

A Midsummer Night’s Press (October 15, 2017)

Reviewed by Allie Spikes

A richly textured and collaborative endeavor, translation illuminates, in a new space, an otherwise unfamiliar place and consciousness. Golan Haji’s poetry collection, A Tree Whose Name I Don’t Know, translated from the Arabic by Stephen Watts and Haji himself, is a searing book of poetry haunted by oppression, dislocation, violence, and longing.

Haji, a Kurdish Syrian, left Syria when he was 34 in 2011, the year the civil war began. A Tree Whose Name I Don’t Know helps to establish the importance of his poetry in Kurdish-Syrian literature in translation. This collection of poems is grounded in Haji’s personal experience as a Syrian refugee. He has worked as a medical doctor, poet, and translator.

Often an expression or rendering of interstitial living, the journey is a key and complex element of diasporic literature. In a less specific context, the journey may evoke the concepts of beginnings, endings, and the movement in between, but in A Tree Whose Name I Don’t Know, the journey is applicable to the whole of the speaker’s experience as a refugee. What would it mean to say such a person has made it, has arrived? In his translator’s note, Stephen Watts writes of his working relationship with Haji:

this shared space being vital because it gives the scope to directly test and coax the fluency, physicality, verve and edge of the poetry into something not too dissimilar in English. When it works…then ‘a happy journey’ is perhaps the most appropriate description of this dialogue of translation, and one that may afford a more life-giving take on the meaning of migration.

In this approach, Watts and Haji have been successful as far as I can tell in evoking reflection on the multi-dimensional refugee experience. For as much as each poem in this collection is intimate and nostalgic such as, “the Kurd and the she-djinn begot children whose skin was white as milk spilt over snow, their fingers tender and pudgy like the cigarettes of mountain folk,” from “The Feather and the Mirror,” each poem is also fluid and timeless, expansive, resisting both representation and limitation at once:

We all are black shadows in this great light, unless the huge fire be damped down. No-one will see us as long as the conflagration is behind us and no-one will see us if we are inside it (from “A Light in Water”).

As an active literary citizen, Haji has collaborated extensively with Estayqazat, the Syrian feminist movement to publish a collection of Syrian women’s voices. As one of the many dimensions of lived refugee experience that Haji renders so beautifully in A Tree Whose Name I Don’t Know, his poem “Snow” embodies Haji’s incisive contribution to feminist literature of survivorship:

You forced me to sit like a half-boiled egg

in the dish of a fevered child,

and you urged me:

“Eat your eyes.

And every night learn how to shut up and to die.”

…

Did you get bored that you amused yourselves terrifying me

and made me wear this mask, pointing at me with raised

eyebrows: this is our clown?

Did you rape me while I was asleep—

under the semen tree

or on a couch you’d tightly tied me to

like the name of a pliers to the plier?

Breathing tightly, encased in slippery yet familiar bark, this poetry collection evokes reflection on the legacy of geo-political turmoil of the Kurdish people without delineating an intellectually overwhelming timeline chock-full of statistics. Originally written in the Arabic rather than the Kurdish, the provenance of Haji’s work itself denotes the layered, multi-dimensional nature of his particular dislocation. The repeating ideas of breath, shadows, distance, trees and longing are often carried, to Watts’s credit, through A Tree Whose Name I Don’t Know, by sound, most notably, the |s| sound—that magic fricative whose song can be said to imitate whisper and wind through trees such as in “Tree Ash”:

The cellar’s a sty full of angels

and drunken sailors.

Their weeping wets the bread and straw

and the smell climbs many stairs

before vanishing.

Then a sweet fragrance spreads:

fire turning cudgels

back into the spans of a peach tree.

Haji’s rendering and Watts’s translation of lived experience meets the breath in my brain before it’s been conceived in my lungs. Dislocation, longing, and the night’s crescent moon haunt A Tree Whose Name I Don’t Know in its relentless journey that never quite arrives, yet Haji’s and Watts’s work has made a home of my mind.

ALLIE SPIKES is a writer and translator who has an MA in English literature and linguistics from Texas Tech University. She is currently an MFA candidate at Western Washington University where she’s working on a book of essays and poems.

Featured image “Peaches” by Andrew Holmes