Calloused Work and Tender Touch

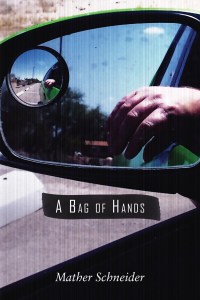

A Bag of Hands by Mather Schneider

A 2017 Rattle Chapbook Prize Selection

Reviewed by Lucas Walker

Pick up this book like you would a bag of hands. The analogy is too easy, I know—but still useful. Unknot the black plastic bag and use your two good hands to open a black plastic circle, look down, look in. Twelve severed hands caught stealing. Mather Schneider asks himself, “What would I not take from this world to give to her?” These poems carefully tell you what he ‘claws’ at when he looks in that bag, what he claws at while driving to McDonalds at three in the morning, what song he hears when his sweetheart’s in the shower. The poems in this book transcend the stench and atrocity of everyday life; they are about the calloused work and tender touch of fingers no matter where they come from, no matter where they’re going, no matter the arbitrary lines drawn between. For Schneider, the arbitrary naturally bleeds into the absurd as he meditates on who gets what and why.

Pick up this book like you would a bag of hands. The analogy is too easy, I know—but still useful. Unknot the black plastic bag and use your two good hands to open a black plastic circle, look down, look in. Twelve severed hands caught stealing. Mather Schneider asks himself, “What would I not take from this world to give to her?” These poems carefully tell you what he ‘claws’ at when he looks in that bag, what he claws at while driving to McDonalds at three in the morning, what song he hears when his sweetheart’s in the shower. The poems in this book transcend the stench and atrocity of everyday life; they are about the calloused work and tender touch of fingers no matter where they come from, no matter where they’re going, no matter the arbitrary lines drawn between. For Schneider, the arbitrary naturally bleeds into the absurd as he meditates on who gets what and why.

Schneider admits that he has stolen, “Hasn’t everybody?” Of course we have. It’s the justification of the thievery that is of interest in these poems. In A Bag of Hands he reminds us to not only consider the hands in the bag but also the ones that “Held the thieves down, the hands that raised the machete.” Who is guilty? Why?

Later, in “Chasing the Green Card”, he’ll revisit culpability in a court room, the stale look of a heartless judge deliberating over who gets to live together, who gets to love each other without interference, without guilt or paranoia. There are insistent and important questions buried in these poems. So Schneider wastes no time, no moment. He steals poignancy from dotted yellow lines, from the tree-crown of a fat, dying Mesquite, from the monkeys screaming in their cages, from his own stumbling through the mundane, clawing questions echoing back. In the whole, these poems are about a “Magic that we couldn’t see coming,” the rough spots of a man-made world, an often times absurd world, “Glued together with kisses.”

Maybe “Loco Love” is absurd, maybe love is what we steal? To not steal for love would be absurd, what else is there? It’s all complicated anyway. Maybe the differential lines between the criminal and the saint, immigrant and citizen, you and I are absurd? Arbitrary lines defy reason. So, what else is there to do but talk through the lines, across the lines, in a language foreign to the tongue—just to feel how the words “Spit and sizzle.” Like Schneider’s Hot Iron Woman, “It’s a delicate operation: To change who you are”, to willingly refuse the authority of an arbitrary line. Maybe the only way to cope with the absurd is to steal? Maybe this is why these poems are asking the question—who gets to say who is stealing what? Who gets to call it stealing?

Either way, you get up every day for 11 years to try and figure it out.

Taxicab philosophy is real. Not just Albert Camus or Kierkegaard. These poems can be read as tenets of means and reason scribbled on scraps of paper blowing through the streets of Tucson, Winesburg, Jalisco. In the poem, “Driving to McDonalds at 3am,” Schneider is yawning his own version of conceptualism as he meditates on love, borders and the wildness of “left handed hummingbirds.” These poems continually address the absurdity of floating the line between countries, between work and money, between him and her, us and them.

Camus’ Absurd Man articulates a Sisyphean quandary and Schneider seems attuned to this. As Camus puts it, the absurd man relies on his courage and reason. Courage teaches him “To get along with what he has, reason informs him of his limits”. [1] Existential strife is defined by limits, lines, borders, possibilities. A Bag of Hands is a beautiful rock rolling up and down the hill, sometimes for no reason at all, just a “Sun barking in a turquoise sky”.

From the start of the book Schneider grapples with the absurd, In “The Zoo” he and Josie, his Spanish speaking love, wander passed glass cages looking instead of talking, it’s easier. “The lemurs have more words in common than we do”. Is it absurd to fall in love with someone even though you don’t know what they’re saying? Not if you remember that this is what you’ve been waiting for, preparing for.

By the time we reach the final poem it is clear how Schneider defines the absurd, and rightly so. “Chasing the Green Card” carefully adopts a Sisyphean push as Schneider articulates the relentless absurdity of the American immigration process. The court room is empty and void…of everything. “They barely allow air.” Futility is pressed into every word of this poem. How is this not a mediation on day to day life, work, bills, getting along? “Waiting without knowing what will happen to you,” in a court room, a taxi cab, behind a McDonald’s counter, walking in a zoo—this is absurd.

And yet…

Schneider doesn’t offer any concrete answer on how to get along in an absurd world other than to bring it back to the hands—yours, hers, his, theirs, mine. Hands grope and feel and work and shape a muddied life. These poems do the same in order to draw attention to the importance of intimacy, of paying attention no matter the futility of the moment, the absurdity of the time. So take notes, listen to the radio, the arrogant rich couple from South Carolina sitting in the back seat of the cab, open the bag of hands because you’re curious and you know your stomach can manage. To do otherwise would be absurd. Participation and love is Schneider’s inadvertent tale, following Camus knowingly or not, “Between the light of gods and the idols of mud it is essential to find the middle path leading to the faces of man”. [2]

[1] Camus, Albert. The Myth of Sisyphus.

[2] Ibid.

LUCAS WALKER is an artist/carpenter/plumber living and working in Bellingham, Washington. He is a MFA candidate at Western Washington University and currently at work on a book of stories/poems.

Featured image titled “Plastic Bag / Ramin Bahrani” by Ars Electronica