An Inexhaustible River: A Conversation with Patrycja Humienik

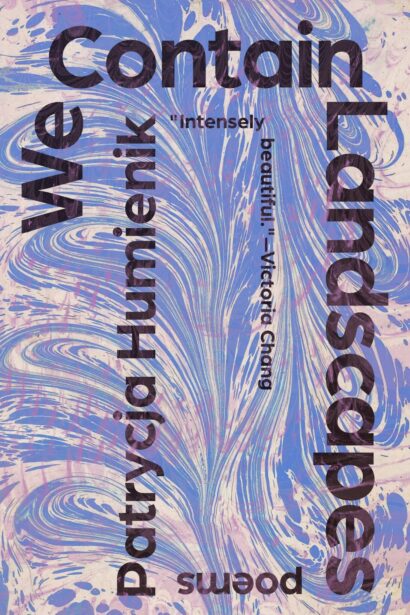

We Contain Landscapes by Patrycja Humienik (Tin House, 2025)

To ask questions not to receive answers, but simply for the pleasure and perversity of asking them—this is the endearing stubbornness of We Contain Landscapes, Patrycja Humienik’s debut collection of poems. This book is propelled by an endless curiosity, shimmering throughout its pages like clear springwater over fragrant stones. Humienik’s poems invite readers to act as cartographers of their own desires, to follow the irresistible pull of wonder across the uncharted and fickle terrains of language, love, and home. As much as these poems flirt with questions without expecting answers, they also tease at the wild what-ifs of experimentation: “If I set fire to the image. Fire clears the land / of excess. But the mind remains / unleveled.” Interior and exterior worlds collapse into each other as readers journey through this speculation on what is within and without our selves.

One of the poems in We Contain Landscapes first appeared in Issue 86, and I remember encountering it as if it had been spoken directly into my ear, from one daughter of Polish immigrants to another. There are few greater joys than unexpectedly feeling seen by a poem, but far more intense is feeling seen and seeing in return. I feel fortunate to have gotten to interview Patrycja about her new book, which invites us all to enter into a relationship with the page that is tender, brave, and embodied. You can watch our video conversation for BR as well.

Miriam Milena: Having followed your work for a few years now, I know you as someone who is really connected to your poetic heart ancestors. I have always loved your “ghost MFA committees” that you’ve posted on Instagram—I think that’s such a good idea!—and I have always admired photos that you take of your books, like amulets, that you have near you, even if you’re not reading them, as you’re working on something. So, in thinking about the legacy of Polish poets that are named in this collection and in your broader work as a poet, I’m wondering if you can talk a little bit about how these ghosts have guided your writing.

Patrycja Humienik: I love that question, and you’re so right that books are also a kind of talisman for me. I do often return to writers long gone. I have such a deep relationship with living writers, and reading is my favorite form of haunting. I love to be haunted by the work of poets who have passed. Before I started my current MFA, where I’m finishing up the semester, I assembled a ghost committee of twelve poets to ground me in the deep, voracious, bold approach to writing that I aspire toward: [Mahmoud] Darwish, June Jordan, Alejandra Pizarnik, Adam Zagajewski, [Wislawa] Szymborska, [Federico Garcia] Lorca, Brigit Pegeen Kelly, Basho, Agha Shahid Ali, Linda Gregg, Audre Lorde, and Lucie Brock-Broido. These are each luminaries that remind me that I’m entering into conversations that are ages old, questions across place and time that have been asked before. They each offer such particular, distinct approaches to the line and image and sound, as well as asking questions that I have been asking and will probably ask for a lifetime. In that sense, like so many have said before, it’s a reminder of not being alone, actually. The beauty and strangeness and intensity of experience—of my own experience and also what I’m after on the page—has a precedent. I’m guided by the mystery in their works. Those writers, among so many others, have a mystery in their work that is inexhaustible to me, and there’s a deep study available to us long after people are gone, with thanks to their words. For me, that was also a way to go into a program and remind myself that no matter the opportunities and failures of institutions, there’s deep study available always, beyond institutions, too.

MM: That’s something that I was so struck by in reading these poems. They are haunted—there’s so many people and so many bodies in all of these poems, all of the time! Shutting my eyes and inhabiting the room of We Contain Landscapes, there are so many people, ghosts, family members, beloveds. With that, in terms of being open to receiving instruction, I also noticed there’s a huge theme of obedience and rule-following and learning how to be, sometimes in violent or rigid ways. I was hoping you could share a little bit about how it feels to write and publish these poems, when it comes to the frame of obedience or risk-taking.

PH: It’s such an astute question, from one immigrant daughter to another. Having grown up Polish and very Catholic and a daughter, obedience is my inheritance, in part. It is what I was taught, it’s the way I was supposed to live, and what I have rioted against, often privately, for decades. I irritated my parents, even at a young age, questioning everything and asking questions that were resisted. You mentioned also the relationship between being taught and receiving instruction and obedience. I do think it’s important to not always conflate those things, because I think if we are receiving deep, meaningful instruction and we’re open to that, a good teacher invites us into deeper questioning, and that’s distinct from obedience.

But returning to that question of obedience and risk, I think I was grappling with those tensions at a really young age. Thinking of my appetite for learning and not being entirely against receiving instruction, but rioting against particular ways of being prescribed a single way to live a life, with religious inheritance and all kinds of authoritarian views of living. But many women who have come before me in my lineage arguably have done as they were told, but they have also found ways to disobey. Risk-taking is also my legacy. Women and people in my family who disobeyed and have taken great risks. I think of my mother and the enormous risk she took in coming to the United States. She was pregnant with me, on her first flight ever, so young, so pregnant, coming to an entirely new life. That’s an unimaginable risk and disobedience from everything she’d known and been told about life, right? So, risk to me is actually also part of my inheritance and it’s so much about not knowing, which to me is essential to writing. Risk and writing feel entwined. It’s fascinating, because my parents and all their great risks are part of my inheritance and how I got here. How could they expect anything other than me continuing to question everything, when the whole starting-up of our life was a question in the first place?

It feels complicated, as you mentioned, to publish this work. It’s at once something that I could not keep resisting and denying in myself, though it took me a long time to get to this place. There’s a line in my book about a good daughter being a secret keeper. It took me a long time to be able to share my writing, as someone who wants to honor and has great respect for everything my parents have sacrificed and what I come from. Especially because I’m not interested in oversimplified narratives about immigrant stories, which can get weaponized in strange ways in this country, conflated or oversimplified. I was wary to write into my own life for a long time. Poetry and relationships with other poets have given me permission. The lyric is such a rich space for me beyond the confessions that are demanded of a more linear narrative mode. I think that the lyric invites me to risk something deeper than just the particulars of my own life and story. In that sense, I feel like there’s play with disobedience, and there’s room for also trying to honor what it is that made me not want to obey when I was younger. In Polish it’s called szacunek, this deep question of respect both in Polish culture and in Catholicism. I don’t want to completely deny its value, so I can honor what came before me and the sacrifices of people in our family. I’m invested in that, but how can I do that and also honor myself? In the book, questions of self-deceit come up so much. If we had more time, it’s something that I want to hear your thoughts on, too, in terms of how you navigate that question. Because writing does end up feeling like this betrayal, and yet it also feels like this legacy we’ve been invited into, even in terms of the rich legacy of Polish poets.

MM: You mentioned szacunek, which makes me think more about the Polish language, which shows up a lot in your poems. I love that you refuse to elaborate, translate, or clarify much of the Polish in this book. What has been your experience with writing across your two languages, or multiple languages, especially given all the complicated relationships that we were just talking about with home?

PH: I have such a reverence for multilingualism and the gorgeously impossible task of translation. Like anyone who grows up speaking multiple languages at home, I had an awareness at a young age of the magical act of translation. The ways we do that in life are so fascinating to me, and so I have a reverence for translators and that impossible act. For the purposes of this book, it was important for me to not overly hold the reader’s hand. I wanted to honor my own relationship to the way that Polish words will surface in my thinking and to connect to other Polish speakers and readers. For those readers, there’s an instantaneous relationship to those words, and for others there are tools for looking up words if they wish to engage more deeply. I love to refuse the urgency with which we increasingly seem to be encouraged to approach written material in this extractive, rushed manner. I want people to be invited to slow down while reading this book.

There’s a lot of reasons why I don’t feel the need to translate Polish words for my reader. To your other question about my relationship to Polish and the legacy of Polish poets that haunt this text, that’s what brought me to poems. Recently, my dad shared a clip of a really young me reciting a poem in Polish for a contest. I was maybe five or six years old, and I’m in the back of the car nervously saying that I just recited this poem by Julian Tuwim. I grew up going to a Polish language school on Saturdays. My parents were undocumented and worked so much, and still they made sure I went to school every day of the week, including on weekends to get that language learning. Because of that, I was able to retain and grow this connection to our language and its literature. I want to study Polish poets more deeply and broadly in the decades to come, and I’m so grateful that it was part of my upbringing and connection to poems, even if when I was younger I didn’t always love being forced to memorize something. But now I’m trying to make a more frequent practice of memorizing poems in English and Polish.

I grew up with a geographic and psychic distance from Poland. I wasn’t able to go there until I was nineteen, so everything about that place was imagined or recounted to me from another time. There were ways that I romanticized or oversimplified things about it, and so I continue to grapple with my relationship to Polish and Polishness, that country and its language. I’m so grateful now for the militant insistence my parents had on me to learn it. I have a real respect for that decision now, looking back on all the constraints that made that a hard choice for them. Growing up having to speak Polish at home allowed me to stay connected to it, and now I’m connecting with living Polish writers and get to speak with them in Polish, like when I was just back in Poland last summer for the first time in ten years. That’s really the gift of language. I just want more hours in a day to keep honoring languages and all they open up for us! And as you say, it is slippery for those of us who are children of immigrants. That’s something that I start to unpack in the book, but really it’s a lifelong question.

MM: I want to turn to the title of the collection. Mostly I want to focus on the role of landscape in your life and writing. Aquatic landscapes are so important to you, and there are so many bodies of water in these poems, especially rivers. This text is an immersive landscape on its own, and to be told as a reader that I am also a container for many landscapes blows my mind! It’s something that I’ve been grappling with, so I’m wondering if you can share about the role of land or water in your process, and if you can tell us about some of the landscapes that you contain.

PH: I’m so here for the frictions that a statement with a “we” brings up, and I’m here for anyone who’s reading this to write to me, disagree with me, we can talk about it!

Place and landscape are a profound source of questioning, inspiration, contemplation, disruption, solace. Like so many children of migration, the question of home is a deeply troubling question. It’s also so rich. At the risk of sounding naive or oversimplifying the complexities of belonging to this earth, we are in relationship to land wherever we live, wherever we come from. I don’t want to diminish the very real differences among people and experiences that I cannot understand, yet amidst climate catastrophe, I’m fascinated and disturbed by the lies of capitalism that we can control it. Putting profit above all else, when deceivingly simple things like clean water and fresh air should be impossible to put a price on. I bow down to the non-human life on this earth, and I’m so curious about what nourishes us. Water is foundational to that.

Rivers are this heartbeat of We Contain Landscapes, and a heartbeat of my preoccupations and obsessions as a writer beyond the first book. Rivers are the veins of the earth. My love for them is just eternal. It is impossible for me to be near one, to look at one or even think of one, and to not be thinking of self and collective, the limits and possibilities of “we”. Rivers are contested sites that bring up so much, in terms of resource and nourishment and borders. The phrase “from the river to the sea” has evoked such rage from people who claim that the demand for Palestinian freedom is violence itself, while turning away from this relentless ongoing violence in Palestine. Still the river reaches for the sea, despite. Rivers at once ground me and widen my questioning. They at once make my questions more precise and wilder. I think about borders, time, movement, possession, scale, interiority, nourishment. I just can’t exhaust it. I feel like water is the site of our most fundamental questions about being alive, materially and metaphysically.

As for landscapes I contain… do we not each contain every landscape? Are there not parts of us we’ve never encountered or unearthed or have not explored? It’s interesting to think about answering this question with, for instance, I definitely have no desert in me. What does that mean, if you have no desert? Or if I have no ocean in me? By nature of just being from this earth, and one day when we die we will be returned to this earth, are we not a part of all of that? I find myself agreeing and disagreeing with myself about these questions. I love thinking about how we contain landscapes, but that doesn’t mean that they are ours. So many brilliant indigenous thinkers, writers, and scholars have interrogated the question of land ownership. I’m really intrigued by my own and others’ relationships to land, and that’s a site of endless questioning for me, even beyond the first book.

MM: I’m so moved by the way you talk about writing as something that is relational, engaging with poetry as relational, relation with the land. I want to talk about the series of poems that are all titled “Letter to Another Immigrant Daughter”. These are in an epistolary mode, so for that reason they are inherently relational. I could not help but also imagine these poems in envelopes traversing landscapes by air or ground or water, wherever they ended up going. I would just love to hear you talk about the process behind writing these pieces, however much or little you want to share about the daughters that they’re dedicated to or what it was like to write these over a period of time.

PH: Letters are this long-held love of mine that I’m trying to make more space for in my life again. I used to have more letter writing practices with people I love. Also, I teach in prisons, and I used to write letters to people in solitary confinement for years, and that’s something I’ve been thinking about returning to. I think even if I’m not writing by hand, the very idea of a letter, of addressing a poem to a beloved, just grounds me differently in language right away.

This series emerged years ago in an exchange with the poet Sarah Ghazal Ali. Our epistolary exchange began in May 2021 after taking this virtual class together with Leila Chatti, before we’d even met in person. I was and still am so compelled by her attentiveness to image and sound and the shared questions we have. In this flurry of texts and voice notes, we bonded over our shared grappling with questions of lineage, inherited faith traditions, the possibilities and limits of the lyric, omissions in family stories, all of that. From there we started our epistolary exchange. I pulled from that exchange for the letter to her in We Contain Landscapes, and then in an aspirational way I wrote toward other immigrant daughter writers and artists in my life. Some of these emerged from conversations I had with each of them, and some were a call for more conversations in the years to come.

Relationships with other immigrant daughters have been crucial to making this book. Reaching intragenerationally pushed me to articulate questions and longings that I’ve been unable to ask intergenerationally, either because people have passed on or because of the delicate nature of asking those who came before us about their stories. There are a lot of layers for immigrant families, chasms between us, so reaching toward other children of immigrants has nourished my writing and life. It’s initiated this ongoing conversation with immigrant children. For me, this first book feels like a reaching toward and anchoring in lifelong devotions. I hope I write letters for the rest of my life.

MM: The way the body appears in this collection feels extremely important. I’d love to know a little bit more about how your many years in embodied arts practices, namely dance and performance, have guided your writing. The body is at the fore of so many of these poems, so how does that embodiment make it onto the page?

PH: Dance is one of my eternal loves. I think the body is a site of mystery and inquiry and experiments and connection, pleasure, pain, limitation, possibility, the whole spectrum of human experience. The study of dance has enriched my life so much that it feels deeply entwined with my writing. The whole sensory experience of poetry feels so embodied to me. It is visual, kinesthetic, and sonic. It engages all the senses. At its best the image does a kind of work that is at once deeply physical and mysteriously imaginative. It moves through us, in the way that when we read something that really hits us, we have a visceral experience. I’m really curious about pausing and noticing that and having a practice of noting that.

Because of various writing and movement workshops that I’ve facilitated, it’s almost trite the way that I’ll say “feel your feet.” I’ll ask people to experiment with sensing where their feet touch the ground or might touch one another, if their legs are all entangled in their chair. Just noticing different body parts while writing is an experiment for me to remember that I’m not just a floating head. I’m interested in questions about the erotic and pleasure and the life force that is desire. That feels like an eternal question of the poets—a living impasse. What do we desire? How do we deny or listen to our bodies while we are alive? How do we root down into the sensuous material of our daily lives? What are the limits of the body? These are all connected to questions of the limits of language, of relation, of place and belonging. The body is a part of that.

Dance has also been an experimental container for asking some of those questions, and whenever I can try to fuse movement and writing, and even experiments of embodiment and writing, it’s really rich terrain. Maybe there’s a friction there, or maybe I do suddenly go somewhere else completely when I’m writing. I’m curious about that. Where do I go? I wish I had a better memory of the composition of all of these poems, because when I look back on the many years of making of this book, it feels like I can’t even tell you how some of it happened. But I know that throughout its composition and revision, I was often having a visceral experience. So, that is forever a curiosity for me, and as I move forward with new work, I’m experimenting with being a little more conscious of that relationship and potential friction between body and language.

Miriam Milena is a current MFA student in Creative Writing at Western Washington University. Her work has appeared in the Bellingham Review and Cola Literary Review. She has received fellowships and support from Brooklyn Poets and the Mineral School. Besides teaching writing at WWU, Miriam also works for Asterism Books.

Patrycja Humienik is the author of We Contain Landscapes (Tin House, 2025). She has developed writing and movement workshops for Arts+Literature Laboratory, Northwest Film Forum, the Henry Art Gallery, and in prisons. Her work can be found in The New Yorker, Gulf Coast, Poetry Daily, Poetry Society of America, The Slowdown Show, and elsewhere.