Poetry as Empathy: A Conversation with Jamie Silvonek

Marginal Verse by Jamie Silvonek (Game Over Books, 2025)

Marginal Verse is Jamie Silvonek's debut poetry collection, which I had the honor of reading as a galley. I was stunned by Silvonek's poems -- which are vulnerable, evocative, viscerally felt, and demanding. I could feel each image pulsate, each line break shatter. Marginal Verse is simultaneously tender and rageful -- a deep exploration into selfhood within the dehumanizing confines of the carceral system. Silvokek's poems speak with frankness and lyricism, staying in the hard-to-say moments with intimate awareness. Each line is insistent via startling synesthesia-filled imagery: “moss grows on my uvula & I know small purple mushrooms line my esophagus.” I am excited to celebrate this book and to share our conversation together.

Jane Wong: I must have underlined every single line as I read Marginal Verse for the first time. Each line is insistent and full of visceral imagery. I felt your words in my gut. Indeed, so much of your imagery is bodily (you start the first poem with "So long since I've been touched/my nerve endings mistake fabric for flesh"). Can you speak to how you arrive at your imagery? What is your process for creating such felt words?

Jamie Silvonek: Wow, what an excellent question! It's a bit of a challenge for me to describe how I arrive at my imagery because much of it occurs just beneath my consciousness awareness. Sometimes a line or an image will spontaneously come to me, and then I attempt to construct a poem around it by interrogating what the image represents. Often, there will be a specific moment, memory, feeling, or thought that I'd like to convey in a poem. I roll the subject around in my brain, welcoming random associations that I can try to translate into poetry. For me, there is often a dreamlike, emotive quality to my writing process. I tend to navigate the beginning stages of writing a poem by feeling and sensing. After I get the skeleton of a poem down, I then become more cerebral and critical of what I'm writing and what it is that I'm trying to express.

JW: Each and every poem feels necessary in this collection. What was the process of making this book like for you? How did it begin and what was your editing process like?

JS: The process of creating this book was simultaneously healing and terrifying. I started writing the poems that appear in Marginal Verse when I was about 16, during a very dark period of my life. I had been incarcerated for about 2 years at that point, and I was only just beginning to process my feelings of guilt, grief, self-loathing, and shame. I was very isolated, both by the conditions of my confinement and by my sense of hopelessness. Writing poetry was an act of survival; it provided me with a means to channel everything that I was carrying, to order the chaos in a way that wasn't self-destructive. In poetry, I found a safe space to metabolize my trauma. Writing these poems was life-sustaining, giving me a sense of purpose and hope for the first time. I started writing poetry solely for myself; I didn't consider the possibility of publishing them, let alone the idea that people would be interested in my work. It took a lot of encouragement for me to realize that being vulnerable, putting our work out into the world, is what fosters empathy and creates change. Years later, my friend Ally Ang helped me edit the manuscript and submit it to publishers. Until that point, I had never actually revised or edited my work in any capacity; I thought that the hardest part of writing poetry was the act of writing itself. I tended to abandon poems after I wrote them, believing that they were as good as they were ever going to be. Working with Ally to edit the manuscript, I learned that poems are rarely ever complete, and that it is infinitely more difficult to revise a poem than it is to write one.

JW: What I especially found powerful was how vulnerable your voice is throughout Marginal Verse -- engaging incarceration, violence, mental health, and trauma with such intimate intensity and rawness. Are there particular poems that were more difficult to write than others?

JS: Some poems were definitely more difficult to write than others; many of the poems in Marginal Verse are about violence, incarceration, mental health, and trauma, as you identified. Though these poems were very painful for me to write, it was also a very helpful part of my healing process, a journey I'm still very much on. I genuinely believe that poetry has the power to help us process our trauma and begin to heal. I say this while also openly acknowledging that there are things I haven't yet had the courage to translate into poetry. I hope that one day I will find that courage, because I believe it's important for us to be vulnerable and honest about the darkest parts of ourselves, the worst decisions we've made, the harms we're responsible for. By concealing these things, we're only perpetuating the cycle of violence by keeping ourselves stuck in a place filled with secrets and shame. Choosing to be good to ourselves, other beings, and our planet requires us to be conscious of our capacity to cause harm. And I believe that poetry can help us with this task.

JW: You also write quite a bit about writing itself and what poems can do ("howling as I birth those words"). I'd love to hear what you've been writing now and what poems can do, especially as a vessel for activism.

JS: Only recently have I started to experiment with form, as well as more long-form poems and sequences. I find it funny how I used to dismiss form as constrictive and outdated, because I've since fallen in love! Recently, I've written a sestina, a crown of sonnets, a couple of ghazals, and I'm currently working on a heroic crown, which is definitely a challenge! I've been adhering to rhyme schemes for both the crown of sonnets and the heroic crown, which I've discovered is forcing my brain to think in different ways. I love it! I'm always eager to learn and challenge myself as a writer. I believe that poetry and art in general are incredible instruments for activism; they help us to build community, connect with people who are different from ourselves, and collectively imagine a better world. In my opinion, poetry has a unique ability to foster empathy in comparison to other mediums. Reading a poem allows you to feel what the speaker is feeling, even if you and the speaker have completely different identities, values, and life experiences. The act of both reading and writing poetry is transformative. As someone who is deeply interested in the contradictions of human nature, I believe that poetry forces us to see beyond the good/bad binary. Poems are an attempt to order and ascribe meaning to chaotic, complex, and confusing forces. As a result, they can help us better understand ourselves and each other. I also think poetry has the power to help us actually feel our feelings, to remain tethered to a place of compassion and empathy, to resist the urge to numb ourselves. As a result of numerous factors including my past trauma, my consumption of news media, and the daily violence of prison, I believe that I have been desensitized to suffering. And this is unacceptable. Poetry helps me resist my survival instinct to numb myself by forcing me to confront and feel my emotions. In this way, I believe that poems can help us be more empathetic beings.

Jane Wong is the Editor-in-Chief of Bellingham Review. She is the author of the memoir Meet Me Tonight in Atlantic City (Tin House, 2023). She also wrote two poetry collections: How to Not Be Afraid of Everything (Alice James, 2021) and Overpour (Action Books, 2016). A Kundiman fellow, she is the recipient of a Pushcart Prize and fellowships and residencies from Harvard’s Woodberry Poetry Room, the U.S. Fulbright Program, Artist Trust, the Fine Arts Work Center, Bread Loaf, Hedgebrook, Willapa Bay, Ucross, and others. She is an Associate Professor of Creative Writing at Western Washington University. She is a proud first-generation college graduate and grew up in a Chinese American restaurant.

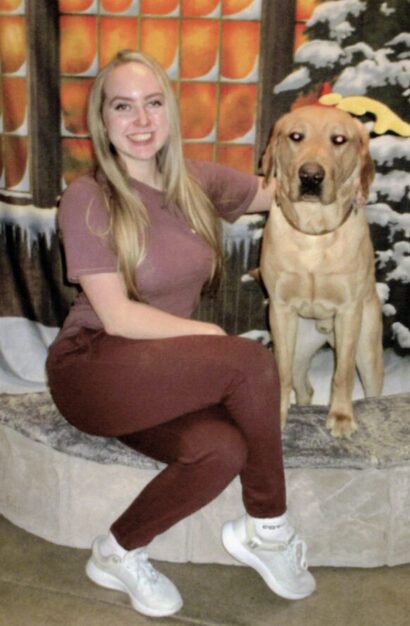

Jamie Silvonek (she/her) is a writer, activist, prison abolitionist, and college student at Ohio University. She has written for The Prison Journalism Project, The Juvenile Justice Information Exchange, George Washington University’s Women in Beyond the Global, and numerous social justice zines. At 14, Jamie was sentenced to 35 years to life in prison, which she is serving at SCI Muncy in Pennsylvania. In her spare time, she enjoys training dogs, tutoring, working out, reading nerdy books, stuffing her face, and challenging misconceptions about incarcerated human beings. Marginal Verse is her first book of poetry.