Arctic Play: A Conversation with Mita Mahato and Michelle Peñaloza

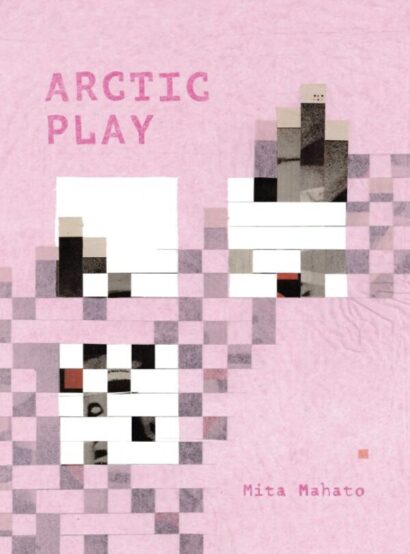

Arctic Play by Mita Mahato (The 3rd Thing Press, October 2024, pre-order here)

Read an excerpt here on BR!

Michelle Peñaloza: What inspired you to create Arctic Play, and how did your experience as a part of the Arctic Circle artist residency in the Norwegian Arctic of Svalbard influence the direction of the project? Did you have any sense of this project before going to Svalbard or did the impetus of what would become Arctic Play spark there?

Mita Mahato: I did have a project in mind going into the residency, but Arctic Play was a detour from it. The residency happened in 2017—the first year of the Trump presidency—and the comix I was making at the time focused on environmental causes, particularly those related to habitats where whales live. I anticipated a residency experience that would feed this direction, but when I got there, it was difficult for me to create much of anything. I saw my complicity in systems that I was critical of—a journey that required the purchase of so much gear, had a significant carbon footprint, and in which I slipped so easily from artist to tourist. And then there was the place, which was so brilliantly enormous. It was so cold, color was weird, light was weird, sound had a quality that didn’t make sense to my ears. I saw plastic litter on the beach that looked like kelp and kelp that looked like plastic. Moon and sun were on the horizon at the same time for what seemed to me like days. It was so strange and fascinating to witness my body learning these new stimuli. But any attempt that I made to write about any of it while I was there, or draw a sketch, flattened the weirdness and the wonder. Similarly, I kept noticing the rush to describe our encounters with the unfamiliar using metaphor—so the sound of a calving glacier became gunshot or thunder. Language felt so displaced and small. The place permeated everything—it was context, subject, everywhere. And I had the thought that we should experience every place like this.

I recently listened to an interview with Amitav Ghosh and he applied the term “terraforming” in a way that I hadn’t heard before and that resonated with some of what I experienced in the Arctic; rather than the sci-fi definition of re-making another planet into an Earthlike place, he talked about terraforming as something that has been happening on Earth regularly in the context of colonialism, where the colonizer “settles” occupied land with what is familiar and comfortable—replacing deserts with lawns or filling swamps with soil. And it occurred to me that this understanding of terraforming could be applied to so much Western scientific, journalistic, touristic, and definitely literary and artistic representations of land, in which encounter is described with the authority of ownership rather than as the slow development of a transforming, symbiotic relationship. And so the Arctic gave me two related questions: How do I not repeat this terrible, objectifying paradigm? And how do I feel into my connection with place rather than separate myself from it? While I was there, the answer was just to be with the place as well as I could. Don’t make anything. Be quiet. And when I returned, the answer was “keep asking the questions”—because they’re relevant everywhere, and maybe especially in places that feel so familiar or so “settled” that you conceive of them as setting or background. Making the book became a way to keep asking these questions.

Just from hearing your answer to these first questions, I feel my mind dilating like it was when I was reading your book! I’m so excited for people to experience it! Ok, haha, back to my questions! You’ve structured the book into three acts, each employing a different visual language. Could you talk about your thinking in framing the book in a theatrical mode? How did you arrive at or determine the three different visual strategies for each act?

The “play” of the title was initially about experimentation. So like the play of “playground”—the joy and surprise of being in a space of play. Make-believe, hide-and-seek, and the gross, yet deeply pleasurable feeling of mud between your toes. Creativity has so much to do with play for me—seeing what erupts when you put this phrase next to this image or write this word in this color. And of course, as well as being fun, play does serious work in how it unsettles, moves, tinkers, tries out. Play can dismantle convention, question why we see things the way we do, and make space to see or do them differently. I think collage, comix, and poetry all invite this kind of playfulness. Making Arctic Play was all about play: playing with the image of the far North and its associations with climate catastrophe; playing with single-use plastic; playing with formal traditions in poetry and comix. And then as I fixed on the title Arctic Play, I thought, “Wait—is this a play? Is this a drama?” And I began seeing how the dramatic arts might have a role in this project. I could create a cast of characters that included icebergs and rocks—sharing their personhood and agency without having to ascribe them with human qualities. I knew I wanted to have three sections—three different attempts or ways to tell stories of encounter. So it started to make more and more sense to call the sections “acts.” I had Shakespeare, García Lorca, and Brecht in mind when I thought about how to “stage” the Arctic in a way that didn’t present it as setting, but a main character that is never static, always moving, churning, crawling. The different visual styles of each act were efforts toward this kinetic expression, making it so the reader’s eye can never settle. I had certain themes and questions I was asking in each act, and slowly the materials and techniques came together. Each act has a different color scheme, and the color choices were inspired by the writings of Josef Albers and Robin Wall Kimmerer. In Interaction of Color, Albers writes about how color is relative and will appear different to our eyes depending on what color is adjacent to it. In Braiding Sweetgrass, Kimmerer contextualizes color theory—and in particular “opposite colors”—within indigenous knowledges. The purples and yellows of the first act are inspired by her discussion of the simultaneous and adjacent blooms of goldenrod and aster. The blues, oranges, and reds of the second act and the pinks and greens of the third act follow suit. Because the book is built on questions, there is so much tension in it. I hope that bringing together these opposed, but complementary colors will invite that feeling of trouble or tension, but in a way that holds fascination and wonder.

I felt wonder throughout the whole book. I really loved the way you created and portrayed the nonhuman characters and also all of the variation in color and materials in each act. I also loved the way PLASTIC plays the part of glaciers and icebergs, NEWSPRINT is rocks and kelp, etc. Can we geek out about materials!? Can you talk a little about the paper and tools you used to create Arctic Play and why you chose them?

You know I love this question! Most of the papers that I use in my practice are discards—newsprint, magazines, old maps. The focus of a lot of my work is loss and so bringing in materials that are no longer perceived as having value has become an important part of my process. They still have presence in the world and acknowledging the vitality of these so-called dead things can open understandings of death and mourning that are so much more expansive than market-driven myths of the value of life. It’s one of the reasons that both of us are drawn to collage, right?—this surprising energy or joy that emerges when grief is channeled through creative acts. The materials that I centered in Arctic Play were wrapping tissues, newsprint, and single-use plastics—like the netting that tangerines or onions are sold in, as well as the plastic bags provided in the produce section. Act 2, which was actually the first act that I made, opens with a group of people collecting plastic trash on the Arctic shore. I knew I wanted to use handmade paper for the backgrounds and I wondered, “What if I included plastics in the paper-making process?”—so I embedded some of these polyethylene grocery shopping remains into the paper pulp. I was so surprised by what I saw when I scanned some of these sheets after they had dried. The digital images had these textures and a sheen that appeared uncannily like glacial ice. And that opened up the opportunity in Act 2 to muse about the weirdness and slippage of metaphor—is it ice or is it plastic? In Acts 1 and 3, I used a lot of colored tissues. It’s a material that I’ve really grown to love working with. It’s delicate and can tear easily, and I had to develop a relationship with it to understand how to work with it: How to feel what it was communicating to my blade and fingers, when to cut slowly, when to cut quickly, when the blade was getting dull and needed to be changed. And then it showed me so much flexibility, adaptability, and personality.

Wow. I love hearing about your relationship(s) to all the materials! I hear so much metaphoricity and so many associations within your process, too. The collage list diagram poems of Act 1, for me, evoked so many associations—flow charts, mazes, timetables, woven baskets, maps, checker boards, color wheels, pixels—and ultimately created an overwhelming feeling of inescapable interconnectedness. Can you tell us about your process and thinking in creating this “woven stage” for the book’s first act?

Wow—I love hearing all these associations. One of the influences of the list poems that make up this act were scientific writings and taxonomies. There’s this assumption that if somebody with the correct pedigree describes something to exhaustion, claiming an objective perspective, we can trust their expertise in it. Their language suggests mastery and then when anyone else wants to learn about this animal, plant, or rock formation, we do so by trusting the expert’s special perspective. Don’t get me wrong— I’m a fan of science. I often collaborate with scientists and I know that there are shifts happening in how academic scientific research is conducted—more room for indigenous knowledges, more room for interdisciplinary work. But the history and legacies of enlightenment science continue to have a negative impact on how environmental issues are often addressed in the West—that is, not as a justice issue, but as a matter to be solved by people in power who will not make changes that would disrupt the systems that have proliferated that power. So the lists in this act, which describe different encounters during the journey—whether that’s with the belongings in my bag or the appearance of birds—present a version of taxonomy that isn’t about ordering, classification, and control. Instead, my hope is that these diagrams expose the impossibility of isolating a being or a phenomenon from its context of entanglements. I wanted to hang these lists on a visual field that would disrupt any mastery that the words suggest. Trying to figure out what that looked like was a challenge until I thought about gridded or graph paper—which also brought to mind the comix grid and how panels are organized on a page and how these panels frame their subjects. And I thought, “Okay what is a paper artist’s version of that?” And then after a few experiments it became apparent that woven paper would be the stage for these poems. Weaving involves entwining, knitting, layering multiple strands. And then there are pieces of the strands obscured by the topmost layers—an underneath that you’re not seeing but is there even so. It was so much fun to map the poems on the gridlines created by the woven paper. All those associations that they brought to mind for you—yeah there’s almost a game there and I’m really excited to hear how readers interact with these pages.

Act 2 in Arctic Play portrays fragmented conversations among passengers. How do you see the handmade papers, plastic scraps, and cut paper images speaking to communication lapses and the human impact on the Arctic environment?

When I think of human impact on the environment (not just in the Arctic, but everywhere), I’m very aware that certain ways of living that are supported by hegemonic, capitalist systems have an outsized responsibility, as well as outsized power. I think about ways of living in the grief of climate catastrophe that aren’t so beholden to them—that acknowledge the conditions in which we live, but aren’t dependent on the systems that are their cause to ease them. I think mutual aid practices are part of how to do that. The 4 scenes that make up Act 2 are retellings of conversations I had during the residency that all deal with the wonder I felt as my body and its senses were adjusting to this strange place. Something that I realized as these communication and sensory lapses continued was just how freeing they were. What happens when I just accept a visual slippage between plastic and kelp? What if lapses aren’t to be filled in, but places to sit and take in? What if fragments are brought into “wholeness” with whatever surrounds them? Act 2 uses metaphor not just to suggest likeness between two things, but to think of those two entities—plastic and kelp or plastic and ice—as entwined, colliding, sharing existence. If we are so lucky to have the time and space to do so, what happens if we give ourselves over to wondering at this weird, heating, plasticizing, acidifying world we live in? Maybe it becomes easier to identify who and what shapes our experiences of it, and who and where should be the recipients of our deepest care.

There is so much deep care throughout Arctic Play. Act 3 presents a visual sonnet centered around a polar bear as the subject of love (which I loved so much!). Can you talk about how this sonnet came to be? I’d also love to hear about your perspective of the challenges and rewards of conveying complex emotions with both language and visual texts.

This act gave me so much trouble and I remade it so many times. I had to remind myself that I wanted to work with the sonnet because it’s a form in which to place a puzzle, not to solve it. We saw a single polar bear from very far away during the journey, but it still lit up my imagination—and I wanted to question why. What is behind the closeness one feels or wants to feel with other animals? Is it love if you’re just gawking at photos that have been doctored in photoshop? Our recording technologies and consumerist habits have made it so we can be in the same room with the photograph of a bear, loving it (the photo) and the meanings we associate with it. But what does it mean to care for a living bear, a wolf, a river system, a sandy beach when your habits are detrimental to its well-being? It’s a big question—and the sonnet at least gives me the space to ask it. There’s a little bit of Christina Rosetti’s “In an Artist’s Studio” in it, but I tried to open the door for the speaker’s muse to leave.

It’s good to consider this question of word and image in the context of this visual sonnet. I’m drawn to comix because of the way the medium invites multiple forms of signification. I love how the best comix use word and image to suggest that there are several ways to look at and understand an emotion, relationship, event, issue. I would say that’s one of the rewards: There is something that is so satisfying in having a place to struggle and play with complexity. But it also suggests one of the biggest challenges: How to bring in enough from tradition or mainstream/popular jargon to create a common basis with your reader. And then how do you do that without relinquishing too much time and space to the questionable values or legacies they may represent?

In talking about Arctic Play you mention that you aimed to create discomfort as a form of care. Can you talk more about this concept? Maybe it also relates to my final question? Ultimately, what do you hope happens to and for readers of Arctic Play?

I hope that readers will see that the book isn’t only about the Arctic; maybe they’ll feel invited to create their own anti-maps or messed-up compasses with which to be with places that are close to or meaningful to them, and also to navigate places that are unfamiliar or challenging. I want to be clear that when I talk about “discomfort as a form of care,” the context of the discomfort is art and hopefully the care extends beyond. I have so many intellectual reasons for why I made Arctic Play and what went into my stylistic choices (many that I’ve shared here). But I also made it while in deep sadness and anxiety about species extinction, habitat degradation, climate injustice, the pervasiveness of factory farming, the plastics that seabirds eat, the increasing impact of wildfire smoke and heat waves, closed borders, genocide. And so it can be an uncomfortable book to read—it’s hybrid and abstract, and then there are these unnamed but palpable threads of sadness that run through it that I’m asking readers to tangle with. But I’m hoping that the book, for these same reasons—its generic weirdness and admission of doubt and grief that so many of us hold—also feels like an invitation to join the play.

Mita Mahato is the author and artist of Arctic Play, forthcoming from The 3rd Thing. Her poetry comix have appeared in places including Ecotone, Iterant, Shenandoah, Coast/NoCoast, ANMLY, and Drunken Boat, as well as in the collection In Between, published by Pleiades. Her mother was Prem, born in Bihar. Her father was Basanta, born in Bengal. She currently lives in Seattle.

Michelle Peñaloza is the author of Former Possessions of the Spanish Empire, winner of the 2018 Hillary Gravendyk National Poetry Prize (Inlandia Books, 2019) and All The Words I Can Remember Are Poems, winner of Persea Books' 2024 Lexi Rudnitsky Editor's Choice Award, forthcoming in Fall 2025. The proud daughter of Filipino immigrants, Michelle was born in the suburbs of Detroit, MI and raised in Nashville, TN. She now lives in rural Northern California.