“The Spirit of Where We Are”

An interview with Katrina Hays and Steven McBurnett

Just as a topographical map offers contour lines and shading to convey the land’s relief, the alliance of poet Katrina Hays and photographer Steven McBurnett conjures the experience of place. Their independent creations of word and image respond to a single physical location, but then come together as a “sametime collaboration” of mutually enriching art. While the poems and photographs are remarkable products alone, the process of the artists evokes an uncommon wholeness—not only in the relations of the visual and verbal arts, but in the vital reciprocity of art and nature. After Katrina and Steven visited Bellingham to present their work, I had the opportunity to learn more about why their collaboration is so special.

Rob Rich, Bellingham Review: There may be more photographers and poets today than ever before, but few work together. Where did you meet each other and what brought out the possibility for collaboration?

Katrina Hays: Years ago, a mutual friend suggested I write poems for a book of Steve’s photography. At the time I didn’t feel I had the poetic chops to match the level of his work, so I sort of skulked away. Much later, we ran into each other again and started talking and the notion didn’t frighten me as much. However, he has so many photos, I didn’t know how to start. The project overwhelmed me. Steve, who is a physicist and engineer by training, came up with an organized way to approach the project: I would look through a set of his photos to see if any of my existing poems might match; and he would look through my graduate thesis to see if he had any existing photos that might link up with specific poems. In this way, we started to get a feel for each other’s work, and also started having a lot of conversations about the nature of collaboration.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/199528589″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Steven McBurnett: One of the things that brought out possibilities for me was when I read Katrina’s thesis and found a line from one of her poems that evoked a memory of a place I’d seen but not photographed. I then went to that place (on the McKenzie River in Oregon) and made the photo. When I printed the image and incorporated a line from the poem as the title for the photo, it worked so well that it opened up my eyes to the potential of collaboration.

RR: How could you tell what made a match?

SMcB: Initially, it was a literal matching. Words about trees equaled image of trees, etcetera.

KH: For me it was more ephemeral. I’d see a photo that evoked a feeling. The jagged juniper tree in the Oregon Badlands that we ended up pairing with my poem “Ontology” gave me a jolt of recognition: tree, odd but absolutely of its place; poem, striving to speak of the “is-ness” of the narrator. It matched somewhere in my gut.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/199528581″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

RR: So how does this process change when you work with new material?

KH: We talked a lot initially—about the nature of collaboration (I am not natively a person who collaborates; Steve collaborated hugely throughout his previous career as a scientist/engineer/manager) and about the orthogonal differences we have in how we approach our arts (visual versus verbal; male versus female; left brain versus right brain). We also talked about how difficult it is for a single art form to really capture the essence of a place. It seemed to us that attempts to reveal the “voice” of a place are often frustrated by the limitations imposed by the tradition of a solitary artist working in a single medium. We tried to approach that problem from a different direction.

SMcB: We came to think of what we do as “sametime collaboration.” What that means is both of us are in the same physical location at the same time, capturing visual and written images while working independently and without much work-related communication during the time of capture. Subsequently, we each refine our individual work and then join the two media into a visual/verbal experience that attempts to give voice to the spirit of where we are.

KH: This really snapped into place for us when we went to Sequoia National Park together in 2014. For days we hiked through these huge trees. I had an enormous emotional response to them—they are deeply moving and humbling—but not one word of poetry was coming through. Steve, on the other hand, was shooting up a storm. Finally, the poem “Lux” just dropped into me, which was such a gift.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/199528571″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

SMcB: Meanwhile, I was struggling with how to get a unique image of such a natural and cultural icon as a giant Sequoia, specifically the General Sherman Tree, which is the largest tree in the world. I wanted to capture the tree in a new light, and it dawned on me to literally do just that. I have a camera modified to shoot in the deep infrared part of the light spectrum, and when I saw the first images from that camera, it looked to me as if I had taken a picture of the soul of the tree. After exploring many compositions, I found the one that most clearly spoke to me. I showed it to Katrina and she showed me her poem, “Lux.” Instant match.

KH: And really magic! “Lux” means “light” in Latin. I wrote that poem not knowing at all what Steve was doing—and when we put the two art forms together, I felt this internal click of “YES.” So, that’s when we really began to get excited about our collaborative work, and started planning trips to places we view as sacred—places that resonate for us, places that touch us deeply.

RR: Wow. That is truly remarkable how the place guides the process. It makes me think of what Gary Snyder says in The Practice of the Wild, that “to know the spirit of a place is to realize that you are a part of a part and that the whole is made of parts, each of which is whole. You start with the part you are whole in.”

I wonder if you had times where the “spirit of the place” was elusive. Are there any practices you have to keep you attentive to it?

SMcB: We haven’t codified it, but now that you ask, there are a number of elements in our emerging practice we use to help us be open to that spirit. One is to seek out times and places where we can have solitude, even if only for a short period of time.

KH: This typically involves alarm clocks (multiple) and coffee. A lot of coffee.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/199528575″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

SMcB: For me, it also involves taking time before I set my camera gear to walk around and just look at the place. Not through a lens, but through my eyes and brain. I try to “see” the place rather than just look at it. I clear my mind of procedure and let my attention wander at random through the landscape.

KH: I tend to operate more from a feeling or emotional platform. To attend is, for me, to get very quiet internally and start paying attention to what messages (and I think of them as messages delivered to my conscious self from some other place within) are coming across the transom, so to speak. I listen, and try to catch the odd thought or impulse. And I always, always, have a small notebook and pen, so even if the odd impulse or message comes when we’re mid-hike from one shooting location to another, I can capture it while we’re underway.

RR: Have you ever found the “spirit of the place” in a landscape that did not at first seem possible?

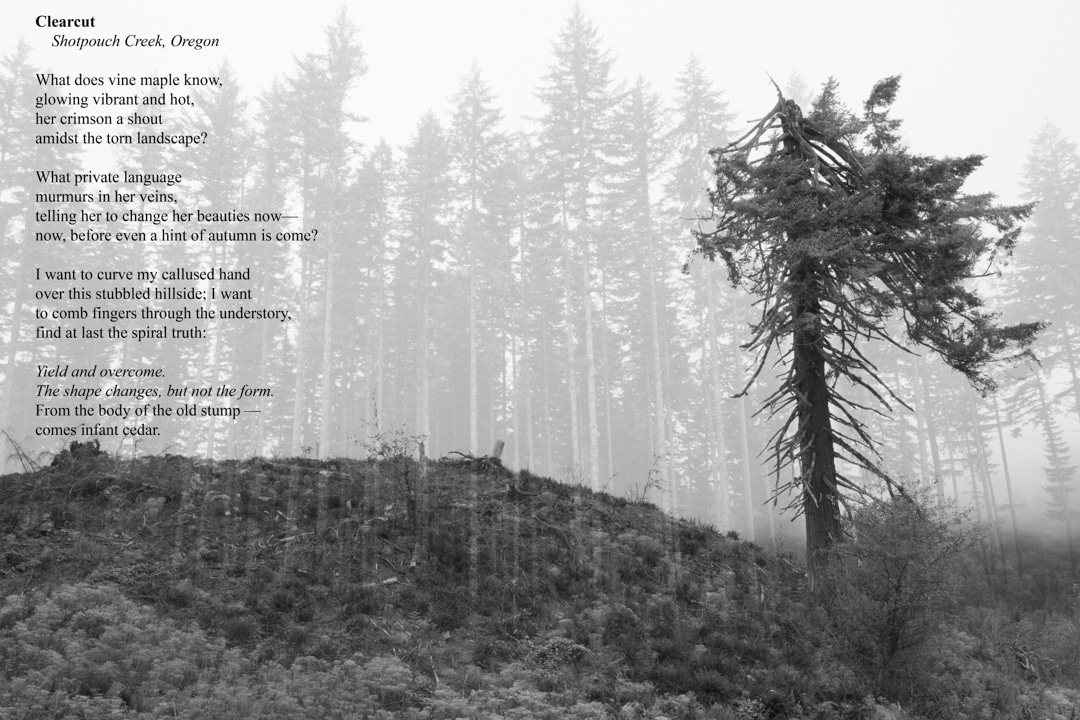

KH: When we did a collaborative residency in the Oregon Coast Range last fall, I asked Steve to get an art shot of a clearcut.

SMcB: My response was that you cannot get an art shot of a clearcut. Period.

KH: But I had this poem that was starting to take shape, and I needed him to come up with something.

SMcB: Katrina was persistent. So, I hiked up into this clearcut several times, and there was nothing there for me. It was awful. But the last time I went up, I spent time doing the seeing thing, and I had an idea that might work.

KH: Again, the result was magic. Steve created a composite that overlaid a semi-transparent image of an uncut forest onto the image of the clearcut.

SMcB: It seems to me the final image contains the forest as it was before the clearcut, the clearcut as it is, and the forest that would grow in the future.

KH: And the poem I wrote was exactly about that sense of trying to find some truth beyond the ugly slash and apparent desolation.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/199528563″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

RR: I can imagine your work would inspire a diverse audience. How do you most like to share your work with others?

KH: Frankly, we don’t have a final answer on this. We did a gallery showing of five collaborations last year, and it was interesting to notice that the poetry was rarely read by viewers. The images instantly grab visual attention, but poems require more time and effort.

SMcB: We’re investigating a number of methods for sharing the work. The classic approach involves printed coffee table books with image and poem presented together, either in original image, limited-edition handbound versions, or more conventionally-printed volumes.

KH: As poetry is—or in my opinion, should be—an aural experience, we’re looking at ways to include the ability to hear the poem while the image is seen. E-books that contain the spoken poem in an audio file might offer this possibility.

SMcB: And we’re also moving towards images that have the poem, or part of the poem, embedded in the image, as “Clearcut” does.

This interview was originally published in Issue 70, as well as the poems by Katrina Hays and the photographs by Steven McBurnett.

ROB RICH is a naturalist and writer based in the Padden Creek watershed of Bellingham, Washington. A finalist for the Sierra Club’s Wilderness 2.0 Essay Contest, his writing has also appeared with Camas, Northern Woodlands, Adirondack Journal for Environmental Studies, The Catch and High Country News.